Nearly two months after COVID spike began, few Midwestern hospitals facing feared surge of patients

Some hospitals nearing capacity, but COVID patients make up small percentage.

Nearly two months after COVID-19 cases began surging in the Midwest, most hospitals there appear to be handling the spike without major issues.

Some hospitals in the region are nearing capacity, but none appear to be receiving a crushing wave of COVID patients after around seven weeks of sharply increasing positive tests.

Hospitalization rates have for several months been one of the key metrics by which public health experts and commentators assess the state of the pandemic in the U.S. Global fears of overburdened medical systems began in March as the world witnessed parts of Italy's healthcare system strain and nearly break under a massive influx of COVID-19 patients.

In the U.S. and in other countries earlier in the year, health care administrators worked aggressively to add surge capacity in hospitals and medical facilities, hoping to avoid the chaos witnessed in certain Italian regions and in other parts of Europe.

Many leaders, meanwhile — including a majority of U.S. governors — announced an open-ended moratorium on what were deemed "non-essential" medical procedures, including cancer screenings and other early interventions, in an effort to ensure hospital space would be free for the expected influx of COVID patients.

In Midwest, nearly eight weeks of spiking cases haven't overwhelmed hospitals

Concerns about a crush of COVID patients were raised anew in early September, when many Midwestern states began seeing significant rises in the numbers of confirmed coronavirus infections.

Yet state-level data indicate that, with the exception of some facilities, most hospitals in that region remain below capacity, even as average COVID cases have soared far above the numbers seen over the summer.

In Iowa, for instance, the state has around 3,100 hospital beds available, with a little over 60% of statewide capacity currently being utilized. Yet the state's coronavirus dashboard says just 12% of total statewide inpatients — 564 as of Wednesday afternoon — were infected with COVID-19, meaning COVID inpatients could theoretically triple there without overwhelming state capacity.

A similar ratio is reported in Nebraska, where about 12% of its hospital inpatients — 436 of 3175 — are COVID-positive. Nebraska is currently filling about 69% of its hospital beds, with a slightly lower occupancy rate in intensive care units.

Both states are either just below or just above the average U.S hospital occupancy rate in 2015, about 65% according to CDC statistics.

Some hospitals see elevated capacity, but COVID doesn't seem to be driving surge

Multiple state-level hospital associations did not respond to requests for comment on their respective COVID outbreaks.

In certain areas of the country, some healthcare systems appear to be under strain, but state data indicate that increasing COVID patients are only partially responsible for it.

In North Dakota, about 86% of hospital beds statewide are occupied. Yet, much like in Nebraska and Iowa, just 11% of inpatients in North Dakota are hospitalized for COVID. In Michigan, meanwhile, the ratio is even lower: Of the 17,302 inpatient hospital beds in use in the state as of Wednesday afternoon, 8.5% of them — 1,479— were "suspected [or] confirmed" to have COVID-19.

John Karasinski, a spokesman for the Michigan Health & Hospital Association, said capacity is not presently an issue in the state.

"Currently, having physical beds available is not a concern, but having enough staff throughout the state to care for and treat those patients is a worry," he said.

"There is national demand for direct patient care staff, including nurses and other clinicians," he added. "Many existing front-line workers are also still recovering from physical and mental stress, as well as trauma, resulting from the first wave. Lastly, community spread is occurring, and healthcare workers are not exempt."

Karasinski highlighted a March statement from Michigan Health & Hospital Association President Brian Peters, who noted that hospitals throughout the state "have emergency response plans that include surge capacity procedures to address an influx of patients."

Earlier hospital fears failed to materialize

Wisconsin is also seeing higher-than-average hospital occupancy rates. The number of hospitalized COVID patients in the state has more than tripled since the beginning of September. Yet, per the state's dashboard, over the last month total statewide hospital occupancy has increased by only about 1.5%.

All told, about 10% of Wisconsin's hospital beds are taken up by COVID patients.

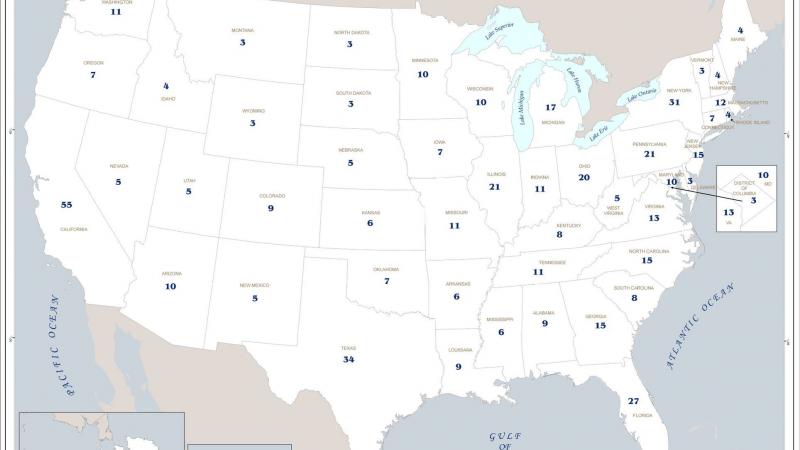

The striking similarities in COVID-to-hospital-bed ratios throughout the Midwest suggests that the pandemic's progress may be largely synced in states within the region. The U.S. has experienced several waves of the disease in successive regions, starting with the Northeast in the spring and moving next to the Sun Belt states in the summer.

In most cases, fears of overwhelmed hospitals failed to materialize. Early on in the pandemic, at the New York City epicenter, certain hospitals saw intensive waves of COVID-19 patients for brief periods of time.

Yet major emergency facilities constructed in New York, as well as a 1,000-bed Navy hospital ship deployed to the city — both intended to handle non-COVID patients and overflow coronavirus cases alike — largely went unused.

That pattern was replicated elsewhere in the country: in Chicago, a $120 million field hospital went largely unused, while both built and planned facilities in other parts of the country were also scrapped for lack of patients.

Fears of collapsed medical systems during the Sun Belt spike over the summer eventually subsided as cases and hospitalizations began dropping rapidly in August. At the peak of Arizona's hospitalization rate, the state had around 12% of its inpatient hospital capacity available. Texas peaked around the same time with about 11,000 COVID hospitalizations in a state with around 65,000 hospital beds.