Judge skeptical of Schiff's argument for keeping impeachment phone subpoenas secret

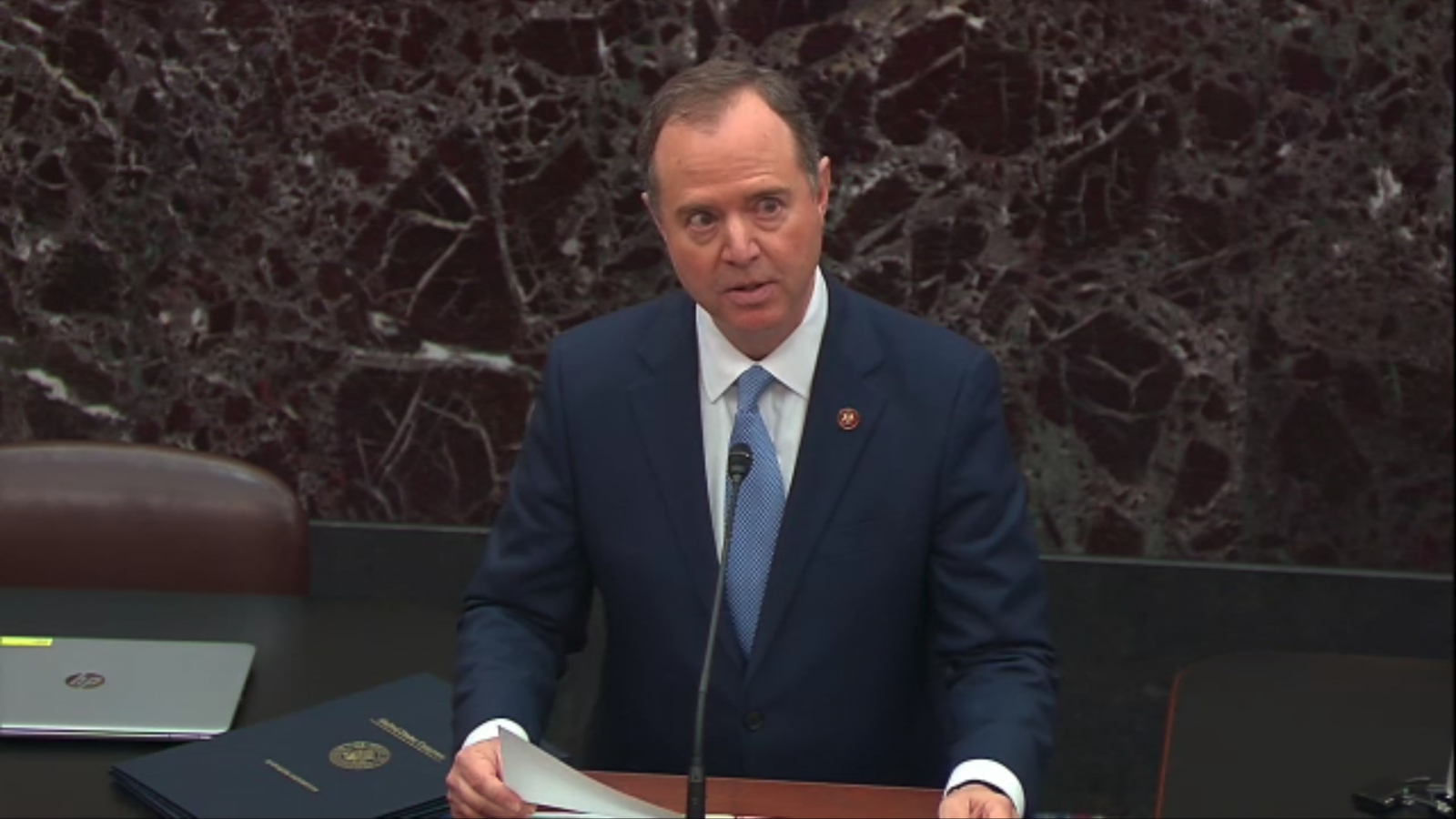

The House Intelligence Committee and its chairman Adam Schiff have not shown legal precedents that justify hiding their subpoenas for a reporter's phone records during the Trump impeachment inquiry, a federal appeals judge said Wednesday.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit grilled the committee's lawyer at a hearing on its decision to publish only certain subpoenas on the committee website. Conservative watchdog group Judicial Watch is seeking the public release of subpoenas to phone companies that targeted private individuals, including reporter and Just the News founder and CEO John Solomon.

Todd Tatelman, principal deputy general counsel for the House of Representatives, argued that the Constitution's "speech or debate clause" shields the committee from being dragged into court to divulge the scope of its subpoenas.

"What's your authority for what you just said?" Judge Karen Henderson responded. "I have not found any case that upholds the speech or debate clause immunity with regard to the common law right of access" to public records. Tatelman admitted he didn't know of any.

The judge also found it "noteworthy," if not "ironic," that Tatelman justified hiding the subpoenas to protect the privacy of irrelevant individuals whose personal information could be exposed. Judicial Watch's entire case is about the committee claiming an "unlimited" power to invade the privacy of individuals, Henderson said.

Judicial Watch is seeking to have the case remanded to trial court to further develop the factual record. Schiff and the committee insist that the Constitution shields them from precisely this sort of litigation to expose their "legislative documents."

The impeachment inquiry report discloses that Solomon spoke with Lev Parnas, an associate of Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani, "at least six times" in the 48 hours before The Hill published an "opinion piece" by Solomon. The report alleges the piece was part of a "smear campaign" against U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Marie Yovanovitch.

The footnote for this source cites documents produced by AT&T but doesn't name the targets of the subpoenas. It simply identifies the committee as the issuer of the subpoena and the date they were issued — Sept. 30, 2019.

What is a "legislative act"?

Judicial Watch intends to shed light on "unprecedented and illegitimate congressional subpoenas" that presume to give lawmakers "unlimited government surveillance power," the group's lawyer James Peterson told the three-judge panel at Wednesday's hearing.

The public deserves to know why the committee is hiding specific subpoenas to phone companies, which prevented targeted individuals from challenging them in court, he said.

"I can't find anywhere in the record" any description of the sought subpoenas other than "certain phone numbers," Judge Henderson said. She asked for any evidence that a subpoena asked for "Joe Blow's phone records" by name. The committee doesn't dispute that it asked for records of individuals by name, including Giuliani, Peterson said.

Court precedents make clear that Congress does not have "unlimited power to issue subpoenas," and Judicial Watch has "more than adequately alleged" that the committee was not engaging in a "legislative act" under the speech-or-debate clause, the lawyer continued.

Judge Robert Wilkins asked if issuing a subpoena pursuant to an impeachment investigation constituted a legislative act. Peterson said it depends, but courts should not bless just "any subpoena." Otherwise, committee chairmen such as Schiff will have "no limit" on their fishing expeditions.

"You can't just plead your way around the speech-and-debate clause" by claiming it's not a legislative act, Wilkins responded. That's precisely why Judicial Watch wants to send the case back to trial court, to develop the factual record, Peterson said.

The subpoenas posted on the committee website are "final official records," and there's a factual question about whether the hidden subpoenas were proper, given the "backdoor approach" used by the committee, the lawyer said.

House lawyer Tatelman seized on Judge Wilkins' point about pleading around the Constitution. Mere allegations of violations of House rules, law or the Constitution are not enough to compel a court order against the committee, he said.

It doesn't matter whether the committee posted only certain subpoenas, Tatelman said: It has "particular reasons" for what it posts, including how many details it includes in the final report. The committee only released information that "makes the connections" between phone numbers and individuals.

Subpoenas intended to "fill in the gaps" from Trump stonewalling

At this point, Judge Henderson brought up the report's coded language about AT&T documents and the date the hidden subpoenas were issued. She questioned the committee's claim that it hadn't actually identified the targets. The committee chose that wording "deliberately," Tatelman said.

The judge also noted that the subpoenas were issued a month before the House impeachment resolution, known as H. Res. 660. Tatelman argued that the impeachment resolution was actually a "procedural resolution" that simply authorized the committee to undertake certain procedures. The impeachment inquiry and oversight of the intelligence community were already ongoing, he said.

The committee is not justifying its actions solely based on Speaker Nancy Pelosi's announcement in early September that committee investigations would proceed, Tatelman told Henderson. Because the investigation was "ongoing" when the sought subpoenas were issued, that shields the documents as a protected legislative act.

Because the Trump administration was not allowing "official records to come forward," the committee used the subpoenas for phone records to "fill in the gaps" from "oral recollections" and incomplete records, Tatelman said: That's indisputably a legislative purpose.

Judge Wilkins asked what limitations on subpoenas could be possible under the House's argument. Tatelman said the pertinent question was whether Judicial Watch could use the courts to compel information from committees.

Judge Henderson said the court must first decide if the subpoenas are public records, at which point it can weigh the public's right to know versus the government's right under the speech-or-debate clause. "I don't think that question has ever been raised before."

The committee has two interests that must be protected, Tatelman said: shielding its investigative sources and methods and protecting the privacy of individuals whose records may be accidentally scooped up.

When Henderson questioned his selective invocation of privacy, Tatelman insisted that the committee drafted its subpoenas narrowly and posted limited information precisely to prevent harm to innocent individuals.

Peterson called his opponent's argument "extraordinarily revealing" by apparently admitting that the phone companies didn't challenge the subpoenas on behalf of their customers. That's not a surprise, because these highly regulated companies are "beholden to Congress."

Like seeking public records under the Freedom of Information Act, this case is about the public's right to know, he said.