‘He was going to respond to the call’: Ex-aides say Ridge’s post 9/11 policies make nation safer

It’s been 20 years since nearly 3,000 Americans perished during the deadliest terrorist attack on national soil. For two of then Gov. Tom Ridge’s top aides – Chief of Staff Mark Campbell and federal policy adviser Mark Holman – the world changed overnight, and their

It’s been 20 years since nearly 3,000 Americans perished during the deadliest terrorist attack on national soil.

For two of then Gov. Tom Ridge’s top aides – Chief of Staff Mark Campbell and federal policy adviser Mark Holman – the world changed overnight, and their boss’s ascent to the forefront of the nation’s response effort was a sudden and somewhat forgone conclusion.

“There were a long of list of cons [for taking the job],” Campbell recalled during a Pennsylvania Press Club event recently. “There might have been one pro, and that might have been patriotism, but I think I realized before we even filled out that list, we already knew the answer.”

So when a joint session of Congress convened one week after the attacks, they braced themselves for what millions of Americans watching did not yet know: President George W. Bush would assign Ridge the task of constructing a brand-new national defense program from the ground up to stop similar attacks before they happen.

“He was going to respond to the call, there was never any doubt in my mind,” Campbell said.

Eventually, that endeavor became the Department of Homeland Security and Ridge its first secretary, until he resigned in 2005. The legacy he left behind, Holman said, continues to this day.

“There’s been six or seven secretaries since him, and they are all very capable,” he said. “But none were beloved like Tom Ridge was, and his presence and calm publicly were key to the beginning of our national security.”

“[DHS] it’s still a baby bureaucracy, but no doubt the nation is safer because of it,” he added.

Indeed, the 22 agencies within DHS manage everything from airline safety protocols to infrastructure protection to border security. Holman said although some of the measures, like those taken to manage airline travel, may be “a pain in the neck … they are also pretty darn effective.”

He also praised the 2001 Patriot Act, the nation’s controversial surveillance program that some critics believe went too far in its efforts to ferret out domestic terrorist activity, as crucial to increasing information sharing between local, state and federal law enforcement agencies and thwarting potential attacks.

“There are so many plots we will never be aware of, some we are, and that’s an incredibly valuable contribution,” he said.

Pennsylvania itself faced an onslaught of threats in the days after 9/11, including rumors that a train packed with nuclear explosives was headed for the Amtrak station in Harrisburg or that terrorists identified Three Mile Island as a “soft target.”

None of those plots ever came to fruition, but some elsewhere in the country did, Holman recalled, like the anthrax-laced mail attacks sent to media and congressional offices that killed four Americans and injured 17 others.

“We had one day on the job, and we had a national biological event,” Holman said. “And it was bumpy and we learned a lot. [It was] a precursor to pandemic planning, how disparate our public health response is, particularly with a bio threat.”

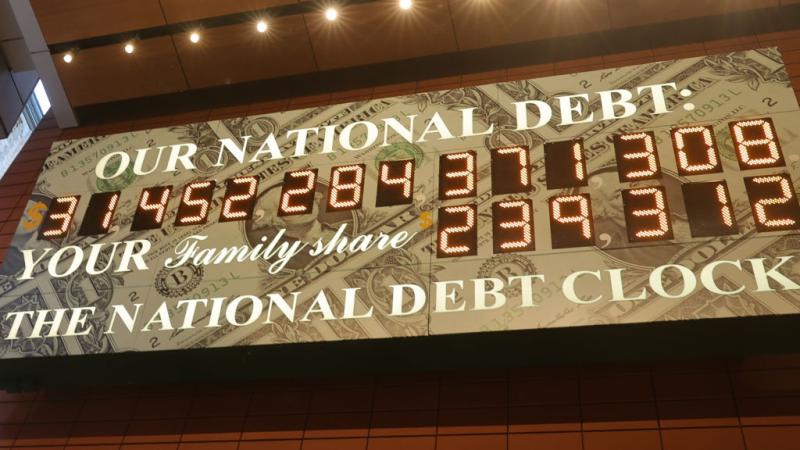

The early days of DHS, then just the Office of Homeland Security, eventually bore a $49.8 billion agency that employs 180,000 who coordinate national defense on a scale the country had never before seen.

In a June 2002 speech, Ridge laid out his vision for DHS during a speech before National Association of Broadcasters Education Foundation, in which he said the responsibility of ensuring “homeland security” at the time fell to more than 100 separate government entities.

“No single agency calls homeland security its sole or even its primary mission,” he said. “Consequently, despite the best efforts of the best public servants, our response is often ad hoc. We don't always have the kind of alignment of authority and responsibility with accountability that gets things done. This creates situations that would be comical if the threat were not so serious.”

In the decades since DHS formed, however, Holman and Campbell say Ridge finds its handling of immigration enforcement – the focus of which has shifted with the political whims of changing administrations – a frustrating “distraction.”

“The political immigration debate has been a bit of a recent albatross for the agency, and it's an entire distraction,” Holman said. “One of the things that bothers the governor most about it is the politics of immigration policy as opposed to the enforcement of immigration policy, legal immigration alike. The two have been lost in one another.”

Even so, Ridge spoke fondly of his premier role in shaping the DHS during a taped reflection on the 20th anniversary of 9/11 published Thursday by PennLive.com.

“At our country’s worst moment, we survived on a uniquely American diet of kindness, generosity and compassion,” he said. “You may not find those words in any national security plan, but I can assure you those concepts are just as critical to our national resilience as any component of our national defense."

“I am profoundly grateful of the opportunity I was given to serve our country, from soldier to secretary,” he said.