Illinois considers funding ‘implicit bias’ and ‘antiracism’ training in schools

Draft proposals “recognize that students of color do not inherently need additional supports by nature of their race/ethnicity, but that these students do face inequities because of historical and existing structures.”

Funding proposals for implicit bias and antiracism training in schools are coming into focus and some see it as an unnecessary controversy that distracts from education in Illinois’ 850 districts.

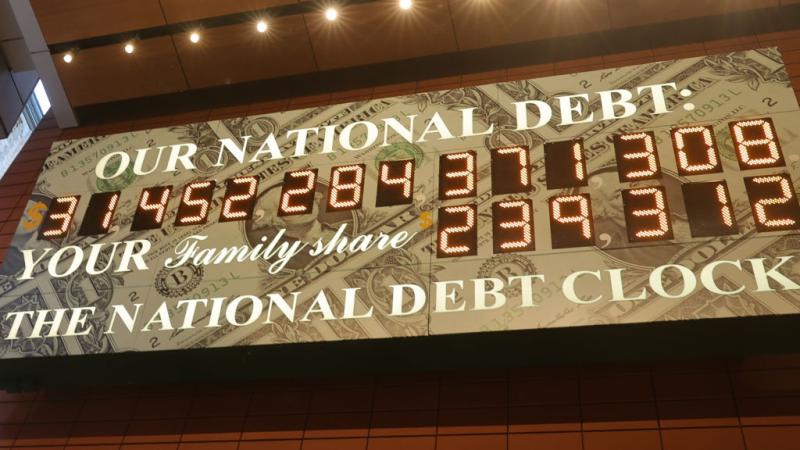

A draft proposal from the Illinois State Board of Education Professional Review Panel set to be considered next month contemplates how to spend an additional $350 million from the evidence based funding model that lawmakers approved several years ago.

There are recommendations for a variety of programs, including teaching foreign languages.

There are also suggestions for “interventions to have more explicit focus on racial dynamic, including equity direct approaches that offer concrete strategies for teachers’ behavioral changes in the classroom and increased bias awareness.”

The draft proposals “recognize that students of color do not inherently need additional supports by nature of their race/ethnicity, but that these students do face inequities because of historical and existing structures, and there is a cost attendant with working to dismantle those inequities through training on antiracism and eliminating implicit bias within schools and districts.”

To address that, the proposal adds “a specific Professional Development cost … related to implicit bias and antiracism at a fixed per-pupil cost based on overall enrollment, with additional per-pupil dollar amount for all students where a district serves over 50% non-white students.”

State Rep. Avery Bourne, R-Morrisonville, said constituents are raising concerns.

“We still have students that aren’t meeting standards in reading and math so I think this is pushing a social agenda in schools that a majority of Illinois don’t support,” Bourne said.

After the controversy of “culturally responsive teaching standards” and new sex-ed requirements, Bourne said the trend is clear.

“The education requirements and recommendations coming out of ISBE have been more and more progressive, more and more pushing a social agenda,” Bourne said.

She said schools should not be advancing what some see as politically divisive.

“We should just be focusing on the best outcomes for kids and funding the schools that need it,” Bourne said.

The proposals from the review panel could be taken up at its next meeting in Springfield on Dec. 6.