Easier said than done: Clean energy goals require large amounts of mining, expert says

A single electric vehicle requires 4,000 pounds of copper, lithium, nickel, manganese, cobalt, graphite and rare earth metals, according to the IEA.

Governments across the globe are demanding a transition to green energy, which includes electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar farms, battery facilities, and immense amounts of transmission lines.

All that hardware will require a large amount of critical minerals, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The U.S. Geological Survey produced a list of 50 of them for the Department of the Interior. The list includes aluminum, cobalt, graphite, zinc, lithium, nickel, rare earth minerals, and copper.

As government subsidies inflate demand for all this infrastructure, supply chains for these minerals are being stretched thin.

A single electric vehicle requires 4,000 pounds of copper, lithium, nickel, manganese, cobalt, graphite, and rare earth metals, according to the IEA.

An offshore wind turbine requires nearly 32,000 pounds of these minerals, half of which is copper.

The problems the copper mining industry faces trying to meet future demand apply to just about every one of them on the USGS list and provides a good example of what the human race will need to accomplish for its clean energy goals.

According to Energyminute, to reach net zero goals by 2050, the world will need 1.4 billion tonnes of new copper. That’s twice the amount of copper that’s been mined in all of human history.

Robert Friedland, billionaire financier in the mining industry, said in a Bloomberg interview last month that copper prices will need to hit $15,000 per ton and remain at that level for a long time before the industry is going to move to satisfy the demand.

For the past year, copper has traded between $7,000 and $8,600 per ton.

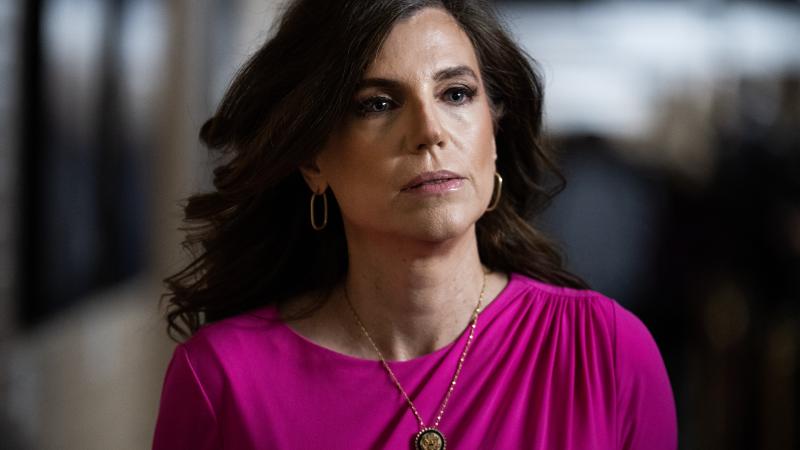

David Hammond, principal mineral economist with the Hammond International Group, told Just The News that the world will need to build a lot of copper mines, which is no small feat.

Economically viable deposits are hard to find, and developing the resources are high-risk investments. So, Hammond said, Friedland’s estimations might be correct.

That means the costs of net zero will be higher than current estimates.

Hammond explained that decarbonizing electricity production in the time frames of a few decades that climate activists want is impossible.

“I call it the Harry Potter syndrome. All these administrators, these people in their 20s and 30s and even 40s — they’ve grown up on Harry Potter. And they think you just kind of wave your wand and it's there,” Hammond said.

He said that 40 years ago, people in the industry who made forecasts of future copper demand weren’t reluctant to provide firm numbers. Those numbers were sometimes a little off, but they followed the general trend lines.

Now, the size of the growth and range of possible numbers tends to make experts less confident about future demand.

“These demand-side drivers seem to be of such magnitude that it’s just given a lot of uncertainty,” he said.

As an example, he pointed to the electric vehicle industry, which is a big driver of copper demand. While automakers and the Biden administration believed demand for electric vehicles would continue to grow, consumer demand isn’t following the expectations, which will impact future copper demand.

According to the International Copper Study Group, the top 20 copper mines in the world produce about half the total copper production today. Some of these mines, Hammond said, have been operating for decades.The Bingham Canyon mine in Utah, for example, has been operating since the late 1800s.

Among the issues that the future copper supply will face is the declining grades of ore available, Hammond explained.

Today, much of the ore that’s mined for copper contains in the neighborhood of 0.5-1.2% copper. Finding more may mean tapping into grades well below that range. A grade of 0.4% is viewed as acceptable for new surface mines.

”But think about how much more material you have to process to get that same amount of copper,” Hammond said.

That means copper prices will need to be much higher to sustain the investment.

Another issue is that mining projects face stiff opposition from environmentalists and Native American tribes. The Center For Biological Diversity, which opposes fossil fuels, also has been fighting against the development of a copper mine in Arizona.

In May, the Biden administration paused the permitting process for another Arizona project, the Resolution Copper mine, which is estimated to hold one of the largest copper reserves in the U.S. Native American tribes have opposed it.

”Even if you have all your permits, and you found a copper mine to develop, it takes 10 to 15 years just to physically get one of these big mines up and going,” Hammond said.

This timeline begins after the exploration process, which he said can take decades.

“You need to throw the dart a thousand times to find one mine,” Hammond said.

He said the mining conglomerate Rio Tinto did a study 30 years ago that estimated about a 1/3000 chance that an explored spot results in a financially feasible mine.

The lengthy permitting process adds to those years and increases the uncertainty of the investment. The litigation that is thrown at proposed projects also increases their costs. All this, Hammond said, makes it difficult to finance mining projects.

It also doesn’t help, he explained that there’s a lack of a coherent mineral policy in the U.S. The Biden administration has made clean energy a cornerstone of its policymaking, yet it has also fought mining projects. Besides the Resolution Copper mine, the administration canceled mineral leases for a copper, nickel, and precious metals mine in Minnesota.

There are still more difficulties in increasing the number of operating copper mines the world needs to meet clean energy targets, Hammond said, such as the lack of knowledgeable advisors informing policymakers and a skilled labor force that could work on any mining projects that manage to get the necessary permits.

Hammond said that it’s not impossible for the industry to eventually meet the expected future demand. The problem is the timelines that policymakers and activists set for the so-called energy transition.

He said that, even if there was the political will to do it, including removing opposition to permitting from environmentalists calling for an energy transition, physically it’s not possible to develop that many mines in a few decades.

“It's not going to happen in the immediate time frame that the climate activists say we've got to do in order to save the planet,” Hammond said.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Links

- immense amounts of transmission lines

- according to the International Energy Agency

- produced a list of 50 of them

- government subsidies inflate demand

- the world will need 1.4 billion tonnes of new copper

- copper prices will need to hit $15,000 per ton

- copper has traded between $7,000 and $8,600 per ton

- Hammond International Group

- consumer demand isnât following the expectations

- International Copper Study Group

- Bingham Canyon

- fighting against the development of a copper mine in Arizona

- Biden administration paused the permitting process

- largest copper reserves in the U.S.

- Biden administration has made clean energy a cornerstone of its policymaking

- the administration canceled mineral leases for a copper, nickel and precious metals mine