Troops fear SecDef Austin's stand-down will single out one form of extremism, ignore others

The Army last fall withdrew an anti-extremism poster that mentioned "white" twice, but omitted other ethnicities.

The pending military stand-down to address "extremism in the ranks" may bring results that go beyond what Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin expected to achieve, according to active duty service members who are scheduled to attend the mandatory sessions.

Austin on Friday ordered all uniformed and civilian leaders in the Defense Department to set aside a day soon to discuss "impermissible behaviors" related to extremism.

"Service members, DOD civilian employees, and all those who support our mission, deserve an environment free of discrimination, hate, and harassment," Austin wrote in the Feb. 5 memo. "It is incumbent upon each of us to ensure that actions associated with these corrosive behaviors are prevented."

Several military personnel who spoke to Just the News said they question whether the mandatory events will focus on politically expedient discussions singling out expansively defined right-wing extremism, while neglecting violent extremism rooted in other political or religious ideologies.

"Is this just the same narrow focus they had to walk back last fall?" one enlisted service member said, referencing a controversial incident from 2020.

In that incident, the Army Provost Marshal General's office produced a graphic image aimed at raising awareness over violent extremism. The graphic was superimposed on a poster, a copy of which was obtained by Just the News. The graphic was posted online, and hard copies were tacked up in military facilities. The image featured the outline of a person, filled with words such as "extremism," "violent," and "supremacist." One prominent word was "white." Another, smaller word also said "white," and another, "neo-Nazi." No other ethnicities nor groups were named.

Following complaints from soldiers who charged that the poster singled out one race, the Army withdrew the poster.

"This was nothing more than an innocent case of bad editing, and as soon as we became aware of the error, the piece was recalled," an Army spokesperson told Just the News. "No offense was intended."

Individual soldiers nevertheless plan to ask about the poster and about reports of recent directives to Special Forces candidates and trainees that they could be kicked out of the Army if they are found to be linked with images that are viewed as extremist. While some of the images — such as Nazi swastikas — clearly are extremist, others have a more prosaic background, and in one case were disseminated by an Army unit as a morale patch.

The Pentagon describes Austin's stand-down as a much needed effort to root out a dangerous trend.

"We are worried that the numbers may be more than what we'd be comfortable seeing them be at this point, and obviously the number should be zero, but I'm saying that the numbers may be bigger than what we may think," Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said last week. "That's what the secretary wants to get after." The Pentagon also wants to define extremism, Kirby said.

But that, too, raises concerns in light of past actions by the Department of Defense, according to one Army National Guard sergeant. "Remember Nidal Hasan, and how that was handled," the sergeant said.

Army Major Nidal Hasan in 2009 opened fire on fellow service members at Fort Hood, Texas, killing 14 and wounding 32. According to eyewitnesses, Hasan, an Army psychiatrist, yelled "Allah Akbar" before launching his attack. Additionally, officials said, Hasan had exchanged emails with a known al-Qaeda recruiter. Nevertheless, in the immediate aftermath of the shootings, the Defense Department couched the attacks not as terrorism, but as "workplace violence."

The Hasan case is worth addressing during the stand-downs, said the National Guard sergeant, who was not present during the Fort Hood shootings but who is "well aware" of what happened.

In light of the Fort Hood shootings, the Army in 2010 formed the Threat Awareness and Reporting Program (TARP). The program teaches soldiers to spot and report suspected espionage, international terrorism, sabotage, subversion, and other matters, and requires them to attend annual training.

Following the Jan. 6 breach of the Capitol, and reports that current and former military personnel were involved, Austin augmented the TARP training, by ordering the stand-down sessions.

"Leaders have the discretion to tailor discussions with their personnel as appropriate, but such discussions should include the importance of our oath of office; a description of impermissible behaviors; and procedures for reporting suspected, or actual, extremist behaviors in accordance with the [Department of Defense Instruction]," Austin wrote in his memo. "You should use this opportunity to listen as well to the concerns, experiences, and possible solutions that the men and women of the workforce may proffer in these stand-down sessions."

Others have objected to the new order, casting it as a political move.

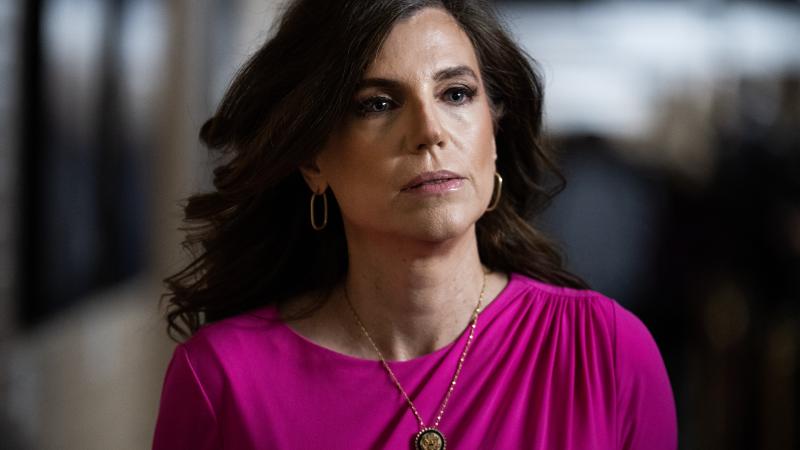

"This is nothing but a political litmus test of our brave men & women," tweeted Colorado Republican Rep. Lauren Boebert, a gun rights advocate. "It is obscene & dangerous to use soldiers who risk their lives for America as political pawns. We can hardly be surprised by these political litmus tests given Biden's political vetting of the 26,000 National Guard troops in DC for his inauguration."

The mandatory discussions are the start of a larger overall effort, Austin wrote.

"This stand-down is just the first initiative of what I believe must be a concerted effort to better educate ourselves and our people about the scope of this problem and to develop sustainable ways to eliminate the corrosive effects that extremist ideology and conduct have on the workforce," Austin wrote.

Austin told the leaders and supervisors to hold their first events within 60 days of the Feb. 5 directive, unless they have been given a waiver by individual service secretaries.