Enduring through war and Depression, Independence Day now threatened by blind hatred of past

Equality has been given a new Marxist meaning. Howard Zinn led the way, teaching students that the Declaration of Independence was a hollow document in the hands of the Founders because it failed to equalize wealth.

In a letter dated July 3, 1776, John Adams informed his wife, Abigail, “Yesterday the greatest Question was decided, which ever was debated in America, and a greater perhaps, never was or will be decided among Men. A Resolution was passed without one dissenting Colony ‘that these united Colonies, are, and of right ought to be free and independent States, and as such, they have, and of Right ought to have full Power to make War, conclude Peace, establish Commerce, and to do all the other Acts and Things, which other States may rightfully do.’ You will see in a few days a Declaration setting forth the Causes, which have impell’d Us to this mighty Revolution, and the Reasons which will justify it, in the Sight of God and Man.”

Adams predicted that “The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America” and “celebrated, by succeeding Generations.” He was off, of course, by two days: The date of July 4, when Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, would be commemorated, in the manner Adams recommended, “as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty” and “solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other. . . .”

Celebrations commenced in some cities the following year, providing an opportunity to proclaim allegiance to the Patriot cause. The Philadelphia Evening Post announced “a day of rejoicing,” with “every mark of festivity,” including troops parading on the Commons and the “firing of feu de joie”.

After the Revolutionary War, celebrations continued with the ringing of bells, the firing of salutes, mustering and parading of volunteer militia companies, prayer and speeches, the reading aloud of the Declaration, music, and feasting.

In 1813, during war again with Britain, the principles of and the anger behind the Declaration were recalled in an announcement describing the plans for the “37th anniversary of American Independence,” in The Columbian of New York City. It recalled “the joy and admiration of the great and good of every nation” marking “rational liberty” and “the triumph of heroic patriotism over tyranny.” That year, during “the rejoicings of the day,” “the aged achievers of our independence” would again “set the example of unanimity” and animate “the youthful supporters of that independence” from Britain, which was “not satisfied with once having been compelled to acknowledge the sovereignty of the American people.”

Of course, another idea — one more historically resonant and universally inspiring than American national sovereignty — also animated the Declaration: the statement that “all men are created equal” and are “endowed with certain inalienable rights.”

As divisions grew over slavery, the North and South each interpreted the Declaration differently, with northerners emphasizing the idea of equality and southerners of sovereignty. The Mobile Advertiser and Register, for example, on July 2, 1861, called the Declaration a “’great State Rights instrument.’”

Beginning as early as the 1790s, however, abolitionists began to use Independence Day to highlight the gap between its meaning and the existence of slavery. Most notable was Frederick Douglass, the former slave, who cuttingly asked in an address in Rochester, N.Y., in 1852, “What to the slave is the Fourth of July?” He mocked the “celebration” as a “sham,” and charged “your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to [the slave], mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy . . .”

Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, in his speech in Independence Hall, in 1861, revealed that his political feelings sprang “from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence,” which gave “hope to the world for all future time.”

In his timeless words at the Gettysburg cemetery, President Lincoln referred back to the birth “four score and seven years ago” of a nation “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” as he predicted “a new birth of freedom.”

Fifty years later at Gettysburg, on July 4, 1913, President Woodrow Wilson highlighted a different facet of the Civil War’s legacy. Wilson, whose record of indifference to racial equality has made him a prime target in today’s battles over American historical memory and monuments, stressed national unity and reconciliation more than Lincoln’s liberty and equality, as he invoked “the gallant men in blue and gray” who reminded the assembled of “how complete the union has become and how dear to all of us.”

President Calvin Coolidge on the sesquicentennial reminded Americans that “The idea that the people have a right to choose their own rulers was not new in political history.” What was “profoundly revolutionary” was the “assertion of the doctrine of equality,” a principle that “had not before appeared as an official political declaration of any nation.”

In the following decade of Depression, celebrations continued, with, for example, in 1936 a parade in Hastings-on-Hudson honoring the 135th anniversary of the birth of Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, Civil War hero. Fireworks and parades took place as elsewhere.

During the Second World War, the Fourth was celebrated, but with attention to war needs. In 1944, the New York Times announced that besides “dances and fireworks” appeals would be made for donations for the Red Cross, the community hospital, and servicemen. In Lake Placid, N.Y. mothers of servicemen, their wives and children, and Gold Star mothers would be honored in parades and services.

During the tumultuous 1960s, celebrations continued. In 1965 the New York Times announced that the Independence Day holiday would be observed with “patriotic rallies, fireworks” and “the traditional holiday double-header” baseball game at Shea Stadium.

The Bicentennial celebrations were more “ambitious than others” in small towns and cities, the New York Times reported. President Gerald Ford, after giving a speech at Independence Hall, then traveled to New York to review the tall ships display from around the world.

But while most Americans were following the wishes of John Adams, another movement was taking place in education, where the idea of equality was being given a new Marxist meaning. Howard Zinn was leading the way, telling students that the Declaration of Independence was a hollow document in the hands of the Founders because it failed to equalize wealth. In his “A People’s History of the United States,” now widely used in schools, he denigrated the Founders and advocated overturning “the System.”

Recently we have seen monuments to Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and Abraham Lincoln targeted by vicious mobs propelled by blind hatred for the past. Rioting has raged across the land.

The mayhem was endorsed in a since-deleted tweet by lead writer for the New York Times’ “1619 Project,” Nikole Hannah-Jones, intellectual heir to Zinn. The statue-toppling advances her cause — replacing 1776 with 1619, the date presumably of the arrival of the first slaves from Africa and when, she proclaims, “it all began.”

To Hannah-Jones, 1619 is the nation’s real birthday. Sadly, it will be for the future generations now being taught with the 1619 curriculum that has been shown by dozens of historians to be deeply flawed, especially the contention that the Revolution was fought to protect slavery.

Independence Day celebrations have endured through war and depression. Is their future now imperiled? If so, John Adams would surely be disappointed. So would Frederick Douglass.

In the same Fourth of July speech in which he scorned the hypocrisy of celebrating liberty in a nation still stained by slavery, the great abolitionist proclaimed his admiration for “the signers of the Declaration of Independence,” calling them “brave men” and “great enough to give fame to a great age.”

The Founders were “statesmen, patriots and heroes,” and “for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory," said Douglass on America’s 76th anniversary.

Aggrieved as he was by slavery’s betrayal of the ideals underlying the founding, Frederick Douglass somehow managed still to draw “encouragement from the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions.”

Statue-topplers and Hannah-Jones, take note from this great American born a slave.

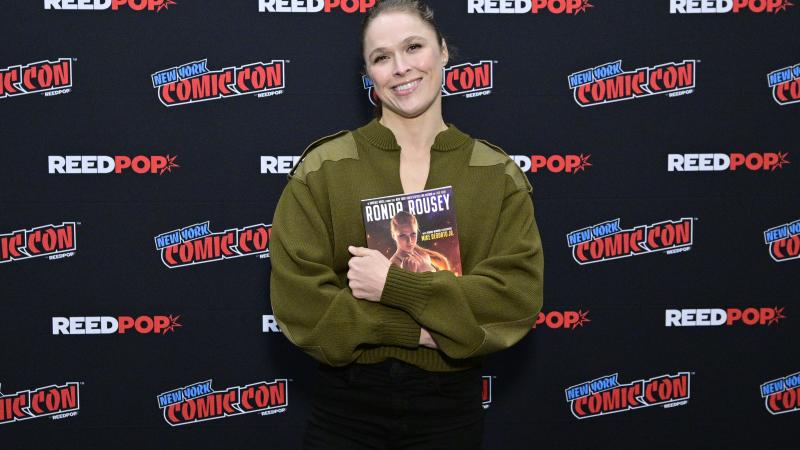

Historian Mary Grabar is the the author of “Debunking Howard Zinn: Exposing the Fake HIstory That Turned a Generation Against America.”