University faces accreditation probe for dumping professor who showed students Muhammad art

Trustees intervening after president dismisses "privileged reaction" from detractors. Her statement shows Hamline University "admitting to retaliating" for one classroom display, free speech group says.

A looming accreditation probe has not diminished Hamline University's zeal to defend its decision to part ways with an adjunct professor of art history for showing students Muslim-commissioned depictions of the Prophet Muhammad, after giving them repeated opportunities to opt out or express concerns.

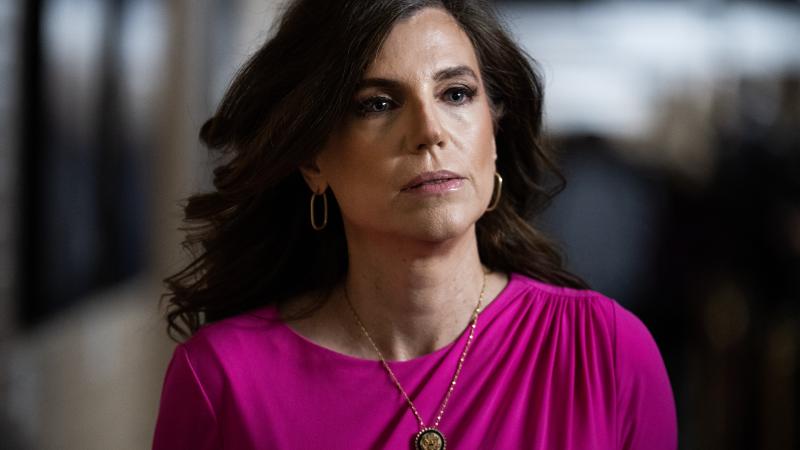

President Fayneese Miller's defiant media statement Wednesday night, which fleshed out her brief New York Times comments and earlier campus statements, threatens to prolong a dispute about both academic freedom but also Hamline's enforcement of an inconsistent strain of thinking within Islam historically.

Hours after the Council on American-Islamic Relations released a statement Friday siding with the nonrenewed professor, Erika Lopez Prater, Hamline's board of trustees said it was "actively involved" in reviewing campus policies and responses to opposing student and faculty concerns about religious offense and academic freedom.

The Minnesota liberal arts school has faced about three weeks of criticism from free speech and academic freedom groups as well as Prater's peers nationwide, among them Hamline's religion department chair.

University of Michigan and Duke professors who teach Islamic subjects told the Times they regularly show Muhammad depictions, the result of a broader push to "decolonize the canon." A petition by one of them supporting Prater had drawn more than 15,000 signatures as of Saturday night.

Hamline is "under attack from forces outside our campus" due to the mischaracterization of a routine nonrenewal as an attack on "academic freedom," according to Miller's two-page statement Wednesday, which puts the term in scare quotes.

While this narrative is "absurd on its face," it has prompted "daily threats of violence" against campus employees, herself and "one of our students," Miller said, possibly referring to Aram Wedatalla, who outed herself as the complainant before the dispute went national.

Media coverage of Wedatalla's tearful press conference Wednesday doesn't mention threats against her. The 23-year-old Muslim Student Association president said her anguish stems from seeing a depiction of the prophet for the first time in Prater's class.

It's not clear whether or how Wedatalla missed the "Religious Observance" section of Prater's class syllabus, which the dumped professor gave to Minnesota Public Radio. The state chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, which is backing Wedatalla, said the syllabus and in-class warnings were irrelevant.

Prater told MPR she has hired legal counsel and wouldn't currently accept another job at Hamline. She plans to teach at nearby Macalester College this spring.

Miller's statement claimed to "correct the record" by denying that Prater had a job to lose in the first place. The adjunct was "most emphatically" not "fired," Miller said, attributing the nonrenewal to "the unit level." The decision "in no way reflects on her ability to adequately teach the class."

The president did not otherwise challenge reporting and comments by Prater and others, including that students were warned again a few minutes before the depictions were shown in the virtual class.

Miller didn't mention communications within campus that suggest the nonrenewal was based solely on that day's class. "In lieu of this incident, it was decided it was best that this faculty member was no longer part of the Hamline community," Associate Vice President of Inclusive Excellence David Everett told the student newspaper in November, for example.

Hamline illustrated the Streisand Effect by hiding critical comments on its Twitter and Facebook pages, documented by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression.

FIRE told Just the News it was sending a "mobile billboard" to campus Jan. 23-24 to accuse administrators of "art censorship," repeating its year-ago stunt against Emerson College for punishing an Asian-led student group that criticized China.

Like Hamline, Emerson scrubbed its social media, the latter by hiding Winnie the Pooh references to Xi Jinping, frequently used by dissidents to mock China's leader.

Emerson didn't publicly respond to the billboard, but "folks on campus" told FIRE it was bothering administrators, campus rights advocacy officer Graham Piro said. The student newspaper also asked FIRE in December — 11 months after the stunt — whether the billboard would come back, he said.

Hamline's accreditor, the Higher Learning Commission, told Just the News it would complete an "initial review" of FIRE's complaint against the university within 30 days of receipt, meaning the first week of February. "This notification will provide information on any next steps, if applicable," public information officer Laura Janota said.

It's not clear whether a single infringement of academic freedom, a condition of Hamline's accreditation, could prompt a full inquiry.

HLC's process "is not designed to intervene in individual matters" but rather to help institutions "gain awareness of systemic problems and improve," its complaint page says. FIRE's complaint only mentions the Prater incident but says Miller has functionally threatened to censor "any teaching that might offend a student's religion."

Miller's statement mocked the writers group PEN America for describing the nonrenewal as "one of the most egregious violations of academic freedom in recent memory."

But while academic freedom is "respected" by Hamline, it must be mitigated by concern for "the traditions, beliefs, and views of students," Miller wrote, suggesting detractors had shown their "privileged reaction."

Echoing her earlier comment that students "do not relinquish their faith in the classroom," Miller implied Hamline itself had a religious liberty defense.

The university is "still closely affiliated with the United Methodist Church," and the campus is littered with Methodism cofounder John Wesley's exhortation to "do all the good you can ... to all the people you can," she said. "To do all the good you can means, in part, minimizing harm."

Hamline does not trumpet the UMC affiliation on its website, however. It's noted on the "fast facts" page but not even clearly described on the dedicated history page, three clicks from the homepage.

Miller's statement makes clear the university "admitted to retaliating" against Prater "based on her pedagogical choices" and considers all adjuncts "expendable," FIRE campus rights advocacy officer Sabrina Conza told Just the News.

Hamline didn't help its students by removing their opportunity "to engage with controversial ideas in the classroom, as faculty — especially adjunct faculty — will choose to censor rather than face punishment should a student be offended by the subjects they teach," Conza wrote.

University spokesperson Jeff Papas declined to answer Just the News questions about Miller's statement, including whether faculty can't teach materials that might offend students with deeply held religious beliefs under any circumstances and whether the social media purge had backfired.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Documents

Videos

Links

- showing students Muslim-commissioned depictions

- New York Times

- petition by one of them supporting Prater

- outed herself as the complainant

- Minnesota Public Radio

- Streisand Effect

- documented by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression

- Emerson College for punishing an Asian-led student group

- FIRE's complaint against the university

- complaint page

- "[s]tudents do not relinquish their faith

- "fast facts" page

- dedicated history page