‘Jetliner a day:’ Pennsylvania leaders take stock of opioid fatality toll

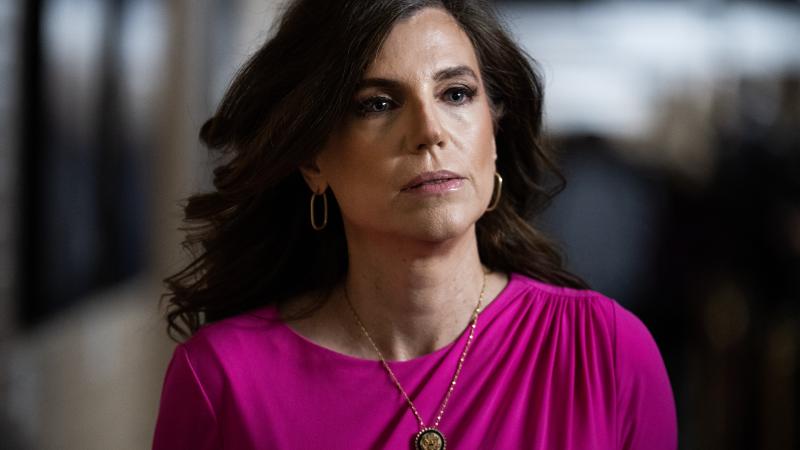

“We know that we are in a crisis point in the country,” U.S. Rep. Madeleine Dean says.

State and federal officials held a roundtable on opioids to discuss the personal effects they’ve felt from the crisis and what can be done to save the lives of more Pennsylvanians.

“We know that we are in a crisis point in the country,” U.S. Rep. Madeleine Dean, D-PA, said. “Last year, 108,000 people died of an overdose, a staggering number. That’s 300 people a day – I call it a jetliner a day.”

In Pennsylvania alone, more than 5,400 residents died of an overdose.

The roundtable, called “Turning the Tide on Opioid Addiction,” brought Dean together along with Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs Secretary Jen Smith, Office of National Drug Control Policy Director Dr. Rahul Gupta, University of Pittsburgh Associate Vice Chancellor for Health Science Integration Dr. Bernard Costello, Democratic state Sen. Art Haywood of Philadelphia, and Republican state Rep. Jim Struzzi of Indiana.

The issue was personal for Dean and Struzzi: Dean has a son who has been in recovery for 10 years, and Struzzi lost his brother to an overdose in 2014.

Discussion centered on how wide-ranging opioid problems are across the state.

"This opioid crisis as we all know is far more than an urban challenge,” Haywood said. “It is urban, it is suburban, it is rural.”

To combat it, stability for those suffering from addiction was crucial, he said.

Getting folks into housing – affordable, safe housing – is, then and now, a serious challenge for putting people on a path to recovery,” Haywood said.

Nor are addiction programs a one-and-done solution. Instead, services for those dealing with substance use disorders need long-lasting support.

“Addiction itself is a disease, and by definition, it is a chronic, relapsing brain disease,” said Smith, the leader of the state's drug and alcohol programs. “Once you go to treatment and enter recovery, it doesn’t mean that’s easy sailing for the rest of your life. It means that every moment thereafter that you walk this earth, you have the potential for experiencing a recurrence of use.”

Creating connections and support structures help those struggling with addiction to avoid drug use, and it shows an approach that recognizes the difficulty of addiction.

“It’s not as simple as saying we need to end addiction. That’s really not realistic,” Smith said. “That’s like someone saying we’re going to end cancer. What we need to do is worry about addressing it from lots of different angles.”

Prevention matters, she noted, as does adequate treatment for those suffering.

All speakers emphasized the problem isn’t one-size-fits-all.

“We need to look at all of those issues: transportation, funding, resources, availability of treatment, and make sure people realize help is available,” Struzzi said. “I think that’s the factor for a lot of people is that they don’t see a way out, and unless you can show them that there is a light at the end of the tunnel, they’re not going to find it on their own.”

Making opioid addiction a state-level priority matters as well.

“From a patient delivery system … our core challenge is getting the services to individuals – and that means we got to pay for them,” Haywood said.

If leaders want more counselors, recovery homes, and mental health treatment, those services will come out of the state budget, he said.

Some services remain controversial, however, and need more educational efforts to explain them. Medication-assisted treatment in county jails and prisons, where prisoners with substance use disorders can access treatment to deal with withdrawals and other effects, is one service that can be controversial.

“There’s still this tremendous need to really educate people about what the use of medication means for individuals with opioid use disorder, and bringing the real-life stories of people who've been positively impacted by the use of medicine in these settings,” Smith said.

She noted that skeptics of medication-assisted treatment raise concerns about cost, but those arguments are not made over the cost of medication for schizophrenia or diabetes.

“We pay for these because we know they are life-sustaining medications,” Smith said.

Gupta, the national policy director, noted the high risk of death from an overdose for inmates who did not get treatment in prison, as well as high levels of recidivism.

“Either way, your community is paying the cost for it in addition to the fact that the majority of people dying is 25 to 54 years of age,” Gupta said.

The economic toll of opioid addiction in 2020 alone was $1.5 trillion, Gupta said, citing a congressional report from the Joint Economic Committee.

“We’re losing the equivalent of Russia’s GDP each year because of a lack of these policies that would help us,” he said.

The roundtable was created by Costello, the Pitt associate vice chancellor for health science integration, and co-hosted by the university.

Something crucial it highlighted was a need for connection and purpose.

“It’s not just the absence of using – it’s finding meaningful work and meaning in your life,” Dean said.