Pennsylvania may ban non-compete agreements for doctors, nurses

Currently, Pennsylvania is one of a dozen states with no restrictions on non-compete agreements.

(The Center Square) — Pennsylvania may ban non-compete agreements for health care workers, ridding the commonwealth of most restrictions on where doctors and nurses can work.

The legislation passed the House in May and awaits action in the Senate.

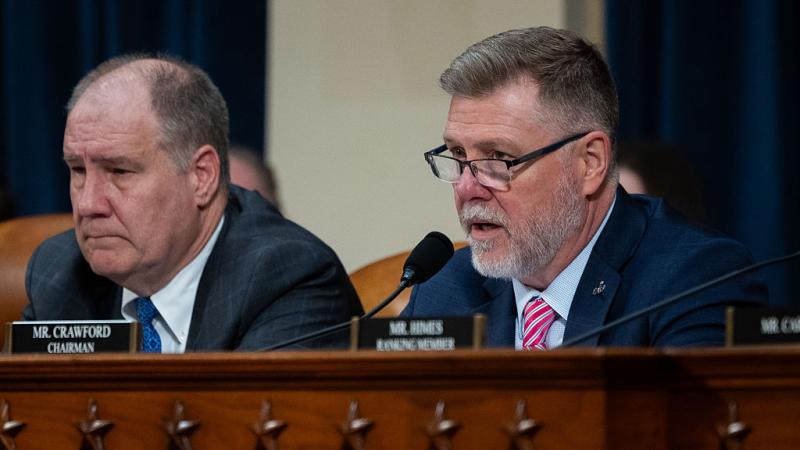

House Bill 1633, sponsored by Rep. Dan Frankel, D-Pittsburgh, would make non-competes void and unenforceable for anyone authorized to practice in health care.

“It’s important in terms of improving or maintaining access for individuals to health care, reducing health care costs, and a general sense of fairness to both providers and patients,” Frankel said.

California, North Dakota, Minnesota, and Oklahoma fully ban non-competes in health care. Others, like Colorado, Virginia, Maryland, Washington, Oregon, Maine, and Rhode Island, restrict non-competes below certain income limits.

Currently, Pennsylvania is one of a dozen states with no restrictions on non-compete agreements.

“Health care workers, whether you’re a physician, nurse, physician’s assistant, whatever, they have so many options, they're in such demand. And if we’re going to retain that workforce, we’ve gotta make that working environment as attractive as possible,” Frankel said. “It’s really a disincentive for Pennsylvania for these valuable, important workers to be able to have the best work environment possible. One of those issues is clearly having the flexibility to make their own employment decisions.”

The bill makes some exceptions. Non-competes would be permissible in counties of the 6th, 7th, and 8th class (which include 34 counties in the state) where the geographic restriction is less than a 45-mile radius and the non-compete is in effect for two years or less.

It would also require employers to notify patients when their provider leaves and how to continue treatment under them or switch to a new provider.

Frankel is hopeful that his bill will get through the Senate, noting bipartisan support in the House when it passed 150-50 (though Republicans were split). The problem can be a live one in Pennsylvania; anecdotally, he noted hearing of cases where a doctor lives in Pittsburgh but commutes to West Virginia due to a non-compete barring them from working in the commonwealth.

“The public is unaware unless they face a situation where they lose access to a trusted provider,” he said. “Once that happens, we hear about it as legislators, but people need to understand that in this current environment, the ability with these restrictive covenants, losing access to that trusted provider is a reality and a possibility.”

Non-compete agreements have attracted national attention since the Federal Trade Commission proposed a ban in January and then issued a rule doing so in April, sparking legal challenges.

“It seems to me, each state has to look at the circumstances,” said Alden Abbott, a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center of George Mason University and a former general counsel for the FTC. “Based on the way they carved out the protection for physicians, what Pennsylvania’s trying seems not unreasonable to me and seems to be striking some kind of balance.”

Laws allowing or banning non-competes, he noted, aim to strike a balance between excessive restrictions that could limit worker mobility and allowing agreements that could mean higher pay or better training for workers in exchange for limitations in the future.

The high levels of regulation in the health care industry, on both the state and federal levels, though, create some bigger issues.

“There’s no shortage of serious problems that could be attacked and I would argue that some of those are more serious for the welfare of workers and patients than non-competes,” Abbott said.