Kids' suicide, mental health hospitalizations spiked amid COVID lockdowns, research finds

University of California San Francisco's COVID response director fears strict protocols in reopened schools will continue mental health problems in children.

COVID-19 policies had disastrous results on children, especially in California, according to medical researchers at the University of California San Francisco.

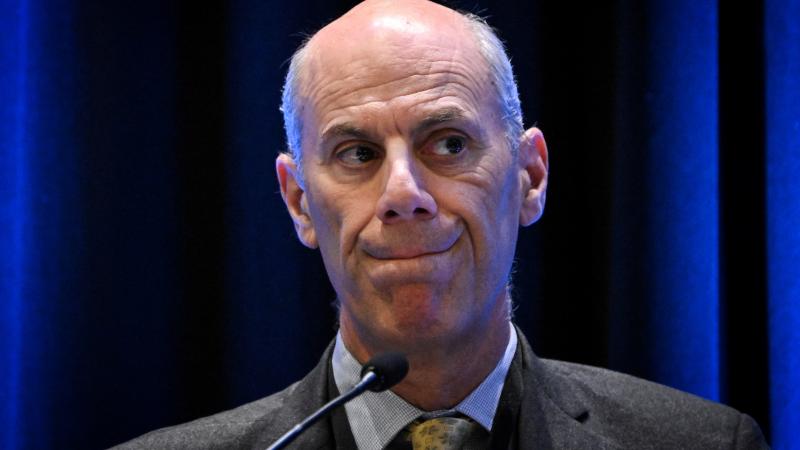

Jeanne Noble, director of COVID response in the UCSF emergency department, is finishing an academic manuscript on the mental health toll on kids from lockdown policies. She shared a presentation on its major points with Just the News.

Suicides in the Golden State last year jumped by 24% for Californians under 18 but fell by 11% for adults, showing how children were uniquely affected by "profound social isolation and loss of essential social supports traditionally provided by in-person school," the presentation says.

Children requiring emergency mental health services jumped last year in Children's Hospital of Oakland, and children's hospitalizations for eating disorders more than doubled at UCSF Children's Hospital. In January, the latter's emergency department (ED) at Mission Bay hit a record for "highest proportion of suicidal children in ER" at 21%.

Noble and her manuscript coauthors previewed their findings and conclusions in a Wall Street Journal op-ed last month. They accused the CDC of burying the harms to teen mental health from lockdown while cherry-picking data to cast teen COVID hospitalizations "in the worst possible light."

The "lessons are national" from California's lockdown policies, which resulted in the longest school closures and highest number of kids out of school, Noble said in a phone interview. "There's evidence of similar trends elsewhere," such as Colorado.

Noble shared an email from the director of a Texas summer camp who predicted a "perfect storm ... of anger and frustration" headed for schools this fall, based on the experience of the camp this summer.

The kids' interpersonal skills have "atrophied" over 18 months in "cloistered" communities. "The shy children are more shy, the anxious kids more anxious, the angry ones are more angry," the director wrote. "Children that tend to miss social cues are missing more of them."

At camps across the country, directors are observing "more mental health struggles than we would expect in 5-10 summers" among the counselors — college students who were also deprived of social interactions and limited to virtual classrooms. Both new staff and "stalwarts" are quitting due to mental health problems, according to the director.

'Worse for kids than the numbers themselves'

Noble's presentation also highlights lesser known CDC data on national trends. ED mental health visits jumped 24% for children 5-11 and 31% for those 12-17 in the first nine months of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.

The change is even more starkly illustrated when contrasting insurance claims for mental health versus all medical claims for children 13-18: The former jumped more than the latter fell in 2020 compared to 2019, particularly early in the pandemic.

Girls have suffered more than boys. ED visits for suspected suicide attempts jumped a whopping 51% among 12-17 year old girls in February and March 2021 compared to the same period in 2019.

Noble said girls even pre-COVID were more active on social media and more likely to suffer from suicidality. They are also slightly younger when they start having mental health problems. She wants to see more research on whether differences in extracurriculars between the sexes plays a role.

Researchers expected to see a drop in emergency visits for mental health in 2020 due to fear of COVID infection and fewer child interactions outside the house, according to Noble. "Things have been even worse for kids than the numbers themselves describe," she said.

The researcher theorizes that interaction through screens is "more foreign and likely unfulfilling from a socialization standpoint" for kids, especially K-3, because most of their waking hours were spent at school. Some who were actively engaged in the classroom "just stopped completely" on Zoom, Noble said, citing her own 12-year-old's difficulties.

Given that the quantitative burden of the pandemic largely fell on adults, who got sick, lost jobs and suffered financially, researchers expected their mental health problems would have "dwarfed" those of kids, who feel these challenges "in an attenuated form," Noble said. Instead it was the opposite, and Noble thinks "prolonged social lockdown" is the likeliest factor.

"Sacrificing the development and well being of our children for enhanced infection control was scientifically unnecessary and ethically unsound," the presentation concludes.

She's now seeking out data from other states to suss out the differences in mental health outcomes for teens based on the relative strictness of COVID-19 mitigations, such as school closures and mask mandates, Noble told Just the News.

Suicide rates may be hard to compare among states and across years because suicides are "traditionally underreported" and stigmatized, and the absolute numbers are small in smaller states. She said a better comparison may be ER mental health visits.

Even comparing large states with vastly different COVID responses, such as Texas and California, could be misleading because of internal variation, especially urban versus rural areas, Noble said. Unexpectedly high ER visits in Texas, for example, "could easily be coming from Austin" or other places where schools remained closed.

While Noble plans to survey kids who came into the ER and their parents about whether they had been in school when it happened, and what role isolation played, "it's a little late in the game" as schools reopen, she said.

Increased 'feelings of isolation'

The researcher fears that strict COVID protocols in reopened schools, which were already cutting into the gains researchers expected to see this spring, will continue the mental health problems in children. Noble called it an "underrecognized" but hard-to-quantify problem.

Parents in many school districts that reopened with "really strict" protocols in the past few months have shared their anecdotes with Noble. Many teens didn't want to return to settings where their interactions were constantly discouraged, and those who did said it "increased their feelings of isolation."

The protocols instilled fear in younger children, who were constantly warned to stay away from each other, she said. Parents reported that masks were preventing them from reading emotions or understanding speech, particularly for those with speech impediments.

These in-school efforts are of limited value, according to the presentation. Researchers have known "for a year and counting" that adults are the "primary drivers" of COVID and kids are "extremely unlikely" to have severe reactions to the virus. Suicides outpaced COVID deaths 20-fold among those 18 and younger in 2020.

Noble told Just the News she's worried that headlines will blare out an uptick in mental health service utilization and child abuse reports when kids return to school this fall, correlating school reopening with harm to children. That misunderstands the role of schools as the primary source of referrals, she said.