Judicial training in climate science raises concerns about creating bias against oil, gas companies

There’s no way for the public to know what judges have participated in the trainings offered by the Climate Judiciary Project, because the group doesn’t disclose which judges it’s trained. However, according to CJP, it’s hosted over 2,000 judges at over 44 events since its founding in 2018.

An effort spearheaded by the Environmental Law Institute to help educate judges on the complex science found in the flood of lawsuits targeting oil and gas companies is raising concerns about the project's neutrality.

Leaders of the institute's initiative, the Climate Judiciary Project, say their goal is to “provide neutral, objective information to the judiciary about the science of climate change as it is understood by the expert scientific community.”

But a new report from the American Energy Institute (AEI) question's whether the initiative is biasing judges against oil companies, who are often the defendants in the cases.

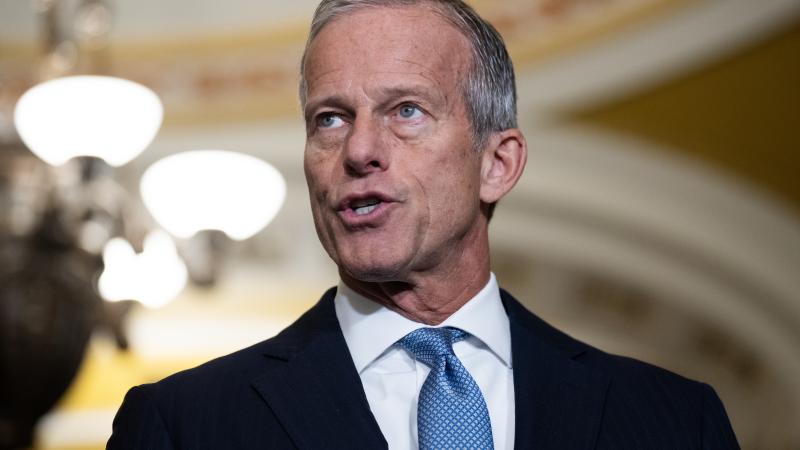

Of particular concern is the partnership between the Federal Judiciary Center and the CJP. The center is a research and education agency for U.S. courts, and it’s chaired by Chief Justice John Roberts.

According to the AEI, the partnership grants the CJP privileged access to federal judges.

Jason Isaac, founder and CEO of AEI, told Just the News that one of his group's calls to action is to break up the partnership.

The CJP “is clearly partisan and embracing a political agenda regardless of the rule of law,” he said.

The Environmental Law Institute told Just the News that the AEI report is "full of misinformation" and that the organization's leadership "spreads false claims about climate science."

"CJP does not take stances on individual cases, advocate for specific outcomes, participate in litigation, support or coordinate with parties in litigation, or advise judges on how they should rule. ELI’s funders include individuals, foundations, and organizations, ranging from energy companies to government agencies to private philanthropies, and none of them dictate our work," the organization said in their statement.

Funding a campaign

A new report from Oil Change International finds that climate lawsuits have nearly tripled since 2015.

With fossil fuels providing over 80% of the world’s energy, David Tong, industry campaign manager for Oil Change International, warns about the potential financial impact on related companies, and subsequently their consumers, as a result of the proliferation of such suit, known as "law-fare."

“The wave of lawsuits against Big Oil could lead to serious impacts on their bottom line, a disincentive for investment in fossil fuel infrastructure, a reduction in corporate value, and a challenge to their social license to continue harming communities around the world,” he said.

There’s no way for the public to know which judges have participated in CJP training and which cases they’ve presided over, because the group doesn’t disclose which judges it’s trained. However, according to CJP, it’s hosted over 2,000 judges at over 44 events since its founding in 2018.

According to the AEI report, the CJP has received millions in funding from entities that are financially backing climate litigation as a means to advance climate agendas.

The JPB Foundation, committed $2 million in funding to CJP and $4.45 million to the Collective Action Fund, which is a project of the New Venture Fund and supports climate lawsuits filed by state and local governments against energy companies.

The Hewlett Foundation, which advocates for transitioning energy from fossil fuels to intermittent wind and solar power, gave $500,000 to the CJP and $150,000 to the Climate Action Fund.

The Wall Street Journal editorial board last month, referring to the AEI report, argued the left has a double standard when it comes to political influence on judges.

Progressives have raised ethics objections when judges speak to conservative groups or attend their seminars, accusing them of having a conflict of interest. Through the Judicial Conference, progressives advocated for a ban on judges from attending meetings of the Federalist Society. Yet, they appear silent as the CJP, which receives funding from anti-fossil fuel groups, provides judges education on lawsuits against oil companies that those judges may be considering in their courts.

“They want this increased transparency into the Supreme Court," Isaac said. "They want full disclosure of every breath that every justice takes and who they're taking it with and around. But clearly they don't want this transparency at the state and lower level federal courts, because that would expose judges that are being really indoctrinated and tainted by this Climate Judiciary Project.”

Jordan Diamond, president of the Environmental Law Institute, responded to the Journal editorial board by saying it made a false equivalence in comparing CPJ to judicial ethics scandals. Those scandals, Diamond wrote, involve judges not reporting gifts.

"The CJP adds science-based educational programming to the lineups of established judicial education institutions," he said.

Climate advocacy

Sandra Nichols Thiam, director of judicial education at the institute, and CJP’s founder Paul Hanle, appear to argue in a 2022 Environmental Law Institute policy brief that the goal of the CJP is to drive climate policy through the courts.

“Climate … lawsuits are critical not just for the parties in the cases but for the many social impacts that will reach far beyond the specifics of a given controversy. Many of these matters gain urgency in view of the lag in policy responses to the challenges posed by a changing natural environment,” the authors state.

The CJP curriculum is similar to the information found on a climate activist website.

It includes modules on “climate justice.” Another module, “Solving the Climate Change Problem,” promotes the wind and solar industry as a solution to global warming, arguing that “solar and wind energy are now the cheapest forms of energy available to human societies.”

It’s not clear how arguing for specific policies is impartial judicial education, but there are many grid experts who would disagree with this claim. It’s presented in the CJP module as indisputable fact without any countering perspectives, or even acknowledgement that they exist.

There’s also a module on attribution science, which is a field of climate science that tries to attribute extreme weather events to global warming. It’s a key component in convincing judges that oil companies are to blame for bad weather.

However, a study last year by Patrick Brown, co-director of the Climate and Energy Team at the Breakthrough Institute, raised serious doubts about the efficacy of this controversial field.

The study came out a couple months after the CJP module was published, but Brown has been criticizing attribution science for some time. The module makes no attempt to suggest that the field has any critics or present their arguments.

Besides the bias in the educational materials the group presents, a board member of the Environmental Law Institute actively advocated for a climate suit to be filed.

Climate Litigation Watch, a project of the nonprofit watchdog Government Accountability and Oversight, obtained emails showing that Environmental Law Institute board member Ann Carlson used a discretionary fund to pay for a trip to a 2019 conference at which she encouraged Hawaii to filed a climate lawsuit based on nuisance laws.

As Isaac said in RealClear Energy, Carlson participated in the conference alongside Vic Sher, who is a trial lawyer representing dozens of states and local governments in their climate lawsuits against energy producers.

In 2020, the city and county of Honolulu filed a nuisance suit against energy providers, and Sher is representing the plaintiffs. When the Hawaii Supreme Court rejected the oil companies' request to dismiss it, they appealed to the Supreme Court, which has asked the Department of Justice to weigh in.

Energy poverty

Steve Milloy, a senior legal fellow with the Energy and Environmental Legal Institute and publisher of “JunkScience.com,” told Just the News that oil companies are terrible at defending against these cases.

“They just don't know how to do it," he said. "They essentially concede the points, and so the judges then have carte blanche to write whatever they want."

If the climate lawsuits are successful, they would likely be to the detriment to consumers and oil companies because they seek billions of dollars in damages that could put some energy companies out of business.

Multnomah County, Oregon, for example, is seeking nearly $52 billion from oil companies, whom the county claims caused a heat dome event in 2021.

While the event brought high temperatures for several days, it didn’t break the state’s record, which was 119 degrees set in 1898. Since that was before significant amounts of carbon dioxide emissions were put into the atmosphere, global warming couldn’t have played any role in the record-breaking heat Oregon experienced that year.

The CJP modules don’t present expert perspectives to the judges participating in these trainings that would speak to the uncertainty and nuance in connecting carbon dioxide emissions to extreme weather events. For the sake of energy costs to consumers, hopefully the defendants’ lawyers will.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Links

- will drive up the cost of everything

- Climate Judiciary Project

- new report

- American Energy Institute

- partnership between

- new report

- JPB Foundation

- Hewlett Foundation

- Wall Street Journal editorial board

- advocated for a ban on judges

- responded to the Journal editorial board

- 2022 Environmental Law Institute policy brief

- CJP curriculum

- climate justice

- Solving the Climate Change Problem

- grid experts

- who would

- disagree with this claim

- module on attribution science

- study last year

- Patrick Brown

- obtained emails

- Ann Carlson

- explains in RealClear Energy

- filed a nuisance suit

- rejected the oil companies' request to dismiss

- asked the Department of Justice to weigh in

- JunkScience.com

- seeking nearly $52 billion from oil companies

- 119 degrees set in 1898

- expert perspectives