U.S.-China emissions agreement continues disparity in approach to climate change

The U.S. reached peak emissions in 2007 and followed it with further emissions reductions, while China’s emissions continue to rise.

The agreement President Joe Biden signed with China this week to reduce carbon dioxide emissions continues a years-long disparity in which the United States has reduced its emissions more aggressively than Beijing.

The deal also is increasing worries among U.S. energy executives that America is being made more dependent on technologies from communist China to drive its green energy production while committing to slow production of the vast oil and gas reserves on its own shores.

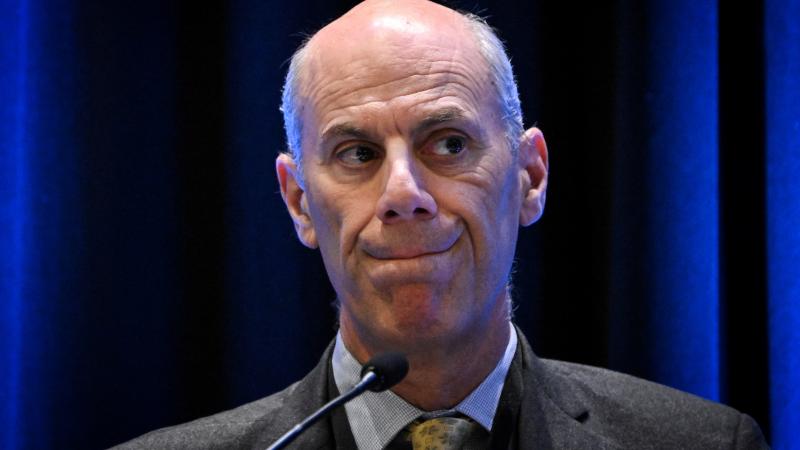

"The bottom line, in short, is the Biden administration said well, look, we're going to push globally to produce less oil, and rely instead on solar panels and batteries and minerals, which are processed in China," Tim Stewart, the president of the U.S. Oil and Gas Association, told Just the News on Friday evening.

"They've essentially said, 'Look, we like you so much, we're going to ensure that you maintain global dominance of these particular markets for the next 30 years. And in return, what we will do to give you that global dominance is to increase our dependency upon you and reduce our ability to produce energy domestically," Stewart said during an interview on the Just the News, No Noise television show. "It's crazy."

Going back as far as the Obama administration, the U.S. and China have signed agreements in which China’s emission reduction commitments are less stringent than those made by the United States. To date, China trails way behind the U.S. in its emission reduction promises.

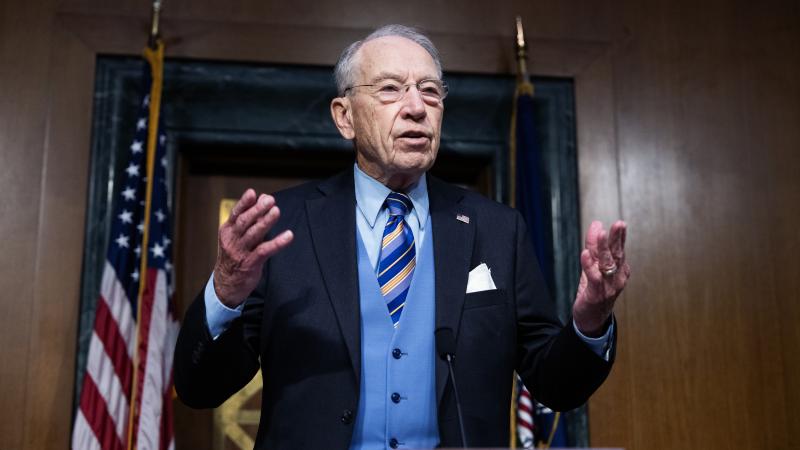

In July, Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry met with China’s equivalent official in Beijing. The trip reportedly failed to result in any formal climate agreement between the two countries.

Tuesday’s announcement that an agreement had been reached referred to that summer meeting. “The United States and China reaffirm their commitment to work jointly and together with other countries to address the climate crisis,” the State Department said.

The latest agreement declared both countries “intend to sufficiently accelerate renewable energy deployment in their respective economies through 2030 from 2020 levels so as to accelerate the substitution for coal, oil and gas generation, and thereby anticipate post-peaking meaningful absolute power sector emission reduction.”

In other words, the countries anticipate emissions in their respective electricity generation sectors to reach a peak and then have “meaningful” reductions. The agreement contained no commitment from China to stop building new coal plants.

The U.S. has long reached that peak and followed it with further emissions reductions, while China’s emissions continue to rise.

Thanks to its development of natural gas resources as a result of the shale revolution, the price of natural gas after 2008 fell to historic lows until the 2020 pandemic. This made it economical to switch from coal-fired power generation to natural gas-fired generation. Natural gas produces less carbon dioxide when burned, and so carbon dioxide emissions, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, fell 33% since their peak in 2007.

China, meanwhile, has greatly increased the amount of power generation from coal since 2016, adding a total 233 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity. Emissions from its electricity sector grew from 2.2 billion metric tons in 2007 to 4.7 billion metric tons in 2022.

Kerry also helped negotiate an emission reduction agreement between China and the U.S. in 2014. According to that agreement, China intended to reach peak carbon dioxide emissions “around 2030,” and it would “make best efforts” to increase its share of non-fossil fuels sources in total energy use to 20% by 2030.

Today, China is nearing 17% of its energy from non-carbon sources, but with its plans to build out more coal plants, it’s uncertain it will reach the 20% target by 2030. China’s overall emissions have increased from 8.5 billion tons in 2010 to nearly 11 billion tons in 2020.

U.S. emissions during the same period fell from just over 5.6 billion metric tons to just over 4.5 billion metric tons.

One year after the first agreement was signed, China and the U.S. once again pledged to reduce their emissions. In that agreement, China committed to reducing emissions per unit of GDP to 65% by 2030, a 60% reduction from 2005 levels. The country has managed a 45% reduction since 2005, while the U.S. has managed a 50% drop.

As Ronald Bailey at Reason points out, the U.S. produces more than twice as much value per unit of carbon dioxide emissions than does China.

Whether or not the third deal is a charm will have to be seen.

Stewart said that these agreements ultimately hand a lot of power to China. Besides taking on the bulk of the emission reduction burden, which Stewart said means “kneecapping” the nation’s oil and gas industry, U.S. renewable energy policy leaves China in control of the minerals required for a growing share of its electricity sector.

“For some reason, Democrats love getting in bed with the CCP. So ‘climate cooperation’ with China likely means the U.S. will keep buying solar panels, batteries, and minerals processed in China and granting complete Chinese market dominance of US firms and supply chains,” he said.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Links

- United States and China signed an agreement

- reportedly failed to result in any formal climate agreement

- Shale Revolution

- fell to historic lows

- economical to switch to natural gas

- according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration

- China has greatly increased

- 4.7 billion metric tons in 2022

- Kerry also helped negotiate

- non-carbon sources

- build out more coal plants

- overall emissions have increased

- once again pledged to reduce their emissions

- 45% reduction since 2005

- 50% drop

- U.S. produces more than twice as much value