Biden spending bill would drive out in-home, faith-based child care providers, critics say

Legislation excludes faith-based providers from building and facilities grants, mandates that preschool teachers have college degrees and wage parity with elementary school teachers.

President Biden's $1.75 trillion spending bill, which the Democrat-led House passed on Friday, contains little-noted changes to child care that critics argue would restrict parental choice, drive out in-home and faith-based providers, and create a one-size-fits-all program.

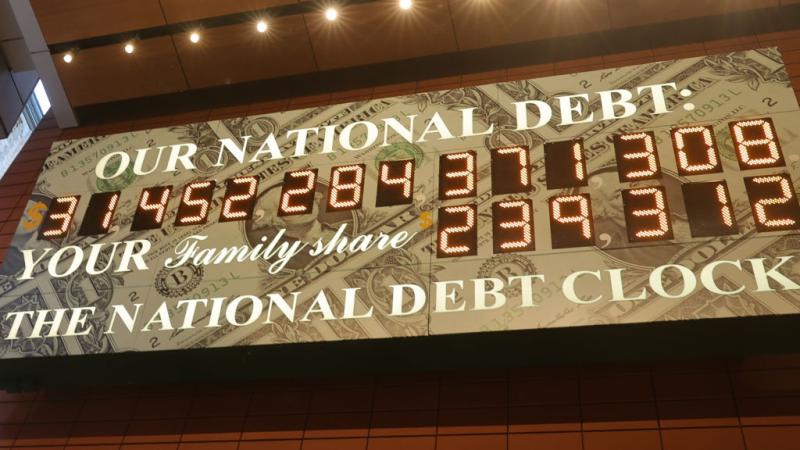

The Build Back Better Act, the largest expansion of the social safety net in decades, invests more than $380 billion in establishing a universal pre-K entitlement and capping the cost of child care for most families at 7% of their income, according to the House Education and Labor Committee.

While supporters have touted the new federal entitlement, critics are alarmed by provisions in the legislation which would tilt the child care playing field decisively in favor of federally subsidized daycare subject to federal strings that would squeeze independent and faith-based providers out of the market.

"The subsidies and additional regulations attached to these federal programs will reduce the options available to parents, as subsidies will only be available to families attending 'approved' government programs," according to John Schoof and Dr. Lindsey Burke of the Heritage Foundation. "Many of the standards and regulations with which program providers must comply are too costly for small, private, and family child care providers."

Repeated surveys show parents overwhelmingly use and prefer family care from trusted individuals over the kind of full-time, center-based care favored by the Build Back Better Act. Even the majority of working parents who use center-based child care opt for a faith-based program, according to the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Three major provisions in Biden's spending bill could prove especially problematic for millions of parents, whose preferred child care may not survive three changes in the legislation.

First, the bill provides grant funding to child care providers for "construction, permanent improvement, or major renovation" — with the explicit exception of faith-based providers.

"Eligible child care providers may not use funds for buildings or facilities that are used primarily for sectarian instruction or religious worship," the legislation states.

Critics argue this provision is discriminatory, allowing for-profit providers to use government money to serve more kids but not faith-based ones.

"This carveout is unconscionable; it's also potentially unconstitutional," write W. Bradford Wilcox and Patrick T. Brown, fellows at the American Enterprise Institute and Ethics and Public Policy Center, respectively. "Progressives are so concerned about one cent of public money going to support the workings of a place of worship that they'd rather bar them from benefiting from money intended to expand child care access."

Traditionally, child care grants have been treated differently than formal federal grants, which necessitate several federal regulations. But, critics note, the Build Back Better Act eliminates this distinction, treating providers that accept subsidies as recipients of federal financial assistance.

This means faith-based providers would have to adhere to a series of non-discrimination regulations should they accept aid. As a result, they may not be able to operate or hire staff based on their beliefs.

"Churches, synagogues, and mosques that still opt to provide subsidized child care thus may be forced to sacrifice the religious character of their programs," writes Max Eden, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

One potential example is religious institutions which teach marriage is a union between one man and one woman. Earlier this year, President Biden signed an executive order directing the Justice Department to enforce Title IX as prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Traditional Catholic child care providers may therefore need to choose between providing subsidized child care and holding onto a core belief.

"It will be detrimental to our ability to participate," said Jennifer Daniels, the associate director for public policy at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. "It would impact our ability to stick with our Catholic mission in a variety of ways."

Supporters of the legislation say such concerns ignore language in the bill permitting subsidies "for sectarian child care services if freely chosen by the parent." They also argue the Build Back Better Act doesn't prevent faith-based providers from teaching religious curricula.

"The language in the bill ... is similar to existing nondiscrimination provisions with which faith-based providers already comply," according to the Center for American Progress. "The Build Back Better Act does not require them to meet any additional compliance obligations or to make any changes to the religious tenets of their programs."

Other proponents of the spending bill are adamant that the statutory changes are necessary to ensure federal money doesn't go to organizations that discriminate.

The second major change in the bill is requiring pre-K instructors to have a college degree.

Specifically, preschool programs that receive federal funding under the Build Back Better Act must "require educational qualifications for teachers in the preschool program including, at a minimum, requiring that lead teachers in the preschool program have a baccalaureate degree in early childhood education or a related field" no later than six years after the date on which a state first receives funds.

However, people who were employed by eligible child care providers or early education programs for three of the last five years and show the state they have the necessary knowledge and teaching skills for the job can bypass this requirement.

Supporters say requiring a college degree is crucial for early education. For example, Steven Barnett, a professor at Rutgers University, has found in his research that preschool teachers with four-year degrees are more effective in the classroom than teachers without four-year degrees.

Critics counter that requiring a college degree hurts small and home-based daycares, where numerous children receive care despite staff often not having a college education. They argue mandating such credentials will make child care less affordable and reduce the supply and diversity of instructors.

The third major change in the bill is requiring states to ensure staff of child care providers receive "a living wage" equivalent to "wages for elementary educators with similar credentials and experience." Such wages, according to the text, must be "adjusted on an annual basis for cost-of-living increases."

These measures would "shore up and strengthen the child care workforce," according to Jane Fillion, press secretary for the First Five Years Fund. Fillion adds that child care workers receive "near-poverty wages, leading to an exodus from the workforce and increasingly limited supply of care options for families."

Others argue that raising wages so sharply will force families — especially those that don't qualify for full subsidies — to pay much more for child care, undercutting one of the central purposes of the legislation.

Last year, the median annual pay for child care workers was $25,460 per year, while the median annual pay for elementary school teachers was $60,660 per year. By these figures, the Build Back Better Act's mandates could require child care providers to pay workers 138% more.

The Center for American Progress calculates the average annual cost of center-based infant care is $15,888 per child, nearly two-thirds of which goes toward paying worker wages. According to Matt Bruenig, president of the People's Policy Project, by factoring in just the new wage requirements, the unsubsidized price of child care would jump to $28,970, an increase of 82% per year.

Rep. Jim Banks, chairman of the Republican Study Committee, referenced Bruenig's findings in an interview with Just the News founder John Solomon last week.

"There's a good chance that the daycare where you drop your kids off in the morning is going to close because of the mandates that are brought about by this bill," Banks said. "But if they don't close, even a left-wing think tank says it will cost you $13,000 more per year."

Congress is out of session this week for Thanksgiving, but when lawmakers return to Washington next week, the Senate will begin debating the Build Back Better Act. Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) said Democrats want the bill done by Christmas.