SCOTUS consensus on divisive issues, including student speech, undermines court-packing push

"These are some major cases where greater divisions were expected," and yet lopsided majorities formed, law professor says.

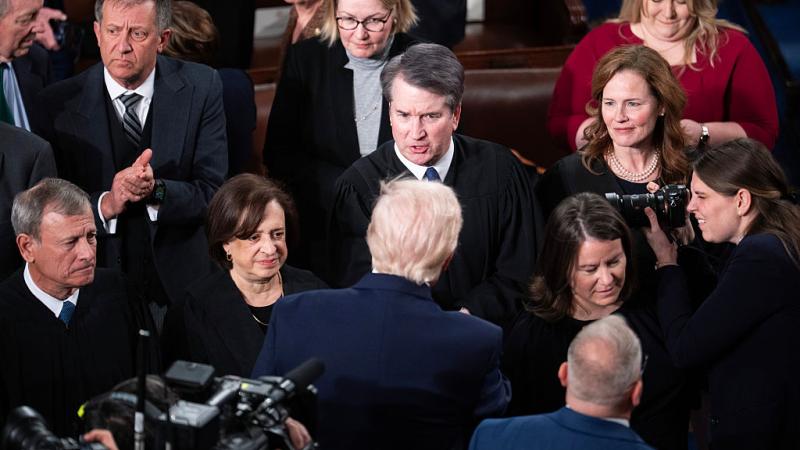

Democratic leaders ran campaigns against the nominations of Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett for the Supreme Court on the basis that they would vote to gut the Affordable Care Act. It didn't happen.

The progressive branch of the party is now promoting court-packing to stop the presumed reign of six conservative-leaning justices, though some legal watchers think it's more of a pressure campaign on the court's swing votes, especially Chief Justice John Roberts.

One thing is clear from the recent spate of lopsided majorities in high-profile and potentially divisive cases: The Supreme Court can find agreement when it wants to.

All but Justice Clarence Thomas agreed Wednesday that K-12 schools can't regulate student speech in contexts that are not school-supervised, including social media outside of of school hours, simply on the assertion that it could conceivably disrupt the learning environment.

The 8-1 tally followed unanimous votes June 21 against the NCAA's limits on educational benefits for student athletes and June 17 against Philadelphia's revoked contract with a Catholic foster care agency that refuses to consider same-sex couples.

Another 8-1 ruling June 18 threw out a lawsuit alleging child slave trafficking in Africa by cocoa product makers Nestle and Cargill. The June 17 vote upholding Obamacare against its latest challenge was 7-2, with Barrett and Kavanaugh in the majority.

Many of the lopsided majorities reached agreement on fairly narrow grounds. The Obamacare challenge failed on conservative states' lack of standing to sue, while student athletes didn't challenge the NCAA's ban on non-educational compensation.

George Washington University constitutional law professor Jonathan Turley saw the same pattern in the student speech case, known as Mahanoy. He wrote that he had hoped for a "bright-line decision protecting student speech" but the court achieved near-unanimity by limiting its reach.

"I do believe that the Court is speaking through these [lopsided] decisions to its critics" who are open to court-packing, Turley told Just the News in an email.

While it often issues "non-ideological and unanimous opinions ... these are some major cases where greater divisions were expected," he said. "The Court is leaving critics with simply outcome-determinate court packing as a rationale for these proposals."

Other legal scholars told Just the News it wasn't clear if recent decisions including Mahanoy reflected the pursuit of unanimity at the expense of useful and conclusive holdings.

"I think the Court is really more of a 3-3-3 institution," Josh Blackman of South Texas College of Law wrote in an email. "The 9-0 topline votes mask a lot of disagreement."

The Philadelphia, Africa and Obamacare rulings revealed "a conservative wing, a moderate wing, and a principle-fluid progressive wing," Blackman argued in a blog post last week. While Roberts "may have been conservative at one point ... he has embarked on a life-long odyssey to pilot the Court to middling moderation," and Kavanaugh is "cut from the same cloth."

"It's hard to read the tea leaves" on whether there was a "conscious effort to get a broad coalition" for Justice Stephen Breyer's opinion in the student speech case, Adam Steinbaugh of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) wrote in an email.

Justices forecast their hesitancy to "identify a bright-line rule about off-campus or online speech" during oral arguments, he said.

'Nurseries of democracy'

Known casually as the cheerleader case, Mahanoy involved a high school student who published a profane weekend rant on Snapchat after she failed to make the varsity cheer squad. It drew dozens of friend-of-the-court briefs.

The Biden administration and school boards supported Pennsylvania's Mahanoy Area School District in its decision to suspend Brandi Levy from the junior varsity squad for a year as punishment for her rant. They said school scrutiny of student speech, wherever and whenever it happens, was necessary to stop bullying and harassment.

On the other side: advocates for religious freedom and the First Amendment rights of students, as well as several conservative states and humorist P.J. O'Rourke.

A ruling in favor of the district would have altered the high court's 52-year-old precedent on speech in K-12 schools, known as Tinker, for the social media era. That ruling prevents schools from regulating student speech unless they can show "substantial disruption" is likely.

In the end, eight justices stuck with the substantial-disruption test as the "baseline" and defined disruption as "something more than controversy or discomfort" that merely affects the school, FIRE's Steinbaugh told Just the News.

His legal analysis said the court's identification of institutional interests and features of off-campus speech also "provides a strong bulwark against censorship" in higher education.

Veteran media lawyer Robert Nelon said the court correctly recognized "some limited circumstances" where off-campus speech unavoidably affects its educational mission. What's different is that high schools and "perhaps" lower schools "must clearly explain how the [speech] regulation meets" the substantial-disruption test, he wrote in an email.

The Mahanoy school district did not come close to meeting its threshold, according to the majority opinion by Justice Breyer, citing severe bullying of students and threats against teachers as appropriate targets of off-campus speech regulation.

The eight-justice majority reined in the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals' broad finding that off-campus speech is inherently immune, however.

The "special characteristics" of the school environment do not "always disappear" when students speak off campus. Especially with the expansion of remote learning, "we hesitate to determine precisely which of many school-related off-campus activities belong" on a list of exceptions to the 3rd Circuit's sweeping rule.

What should guide schools and courts are three considerations about the nature of off-campus speech, Breyer wrote for the majority.

"Geographically speaking," schools rarely serve a parental function when students speak off-campus, he explained. Students may lose the freedom to engage in certain kinds of speech "at all" if schools are monitoring them off-campus, and schools have a "heavy burden to justify intervention" when this speech is political or religious.

Educational institutions also must take seriously their citizenship role. "America's public schools are the nurseries of democracy," Breyer wrote, and the free exchange of ideas — especially those that are unpopular — makes for an informed public, which "helps produce laws that reflect the People's will" when communicated to lawmakers.

Not only did Levy not identify the school or any person in her rant, but her audience was her private Snapchat group of friends.

The most the district could show is Levy's comments were discussed in class for under 10 minutes across "a couple of days," and that some teammates were "upset" by it, the majority found. One of her coaches said that far from threatening team cohesion, as the district claimed, Levy's comments didn't create a disruption at all, Breyer noted.

"Putting aside the vulgar language," Levy's rant criticized the team, coaches and school — "the rules of [her] community" around cheerleader tryouts, as Breyer put it. Such commentary falls squarely within the First Amendment, and the school offered no evidence of a broader effort to stop students from cursing outside the classroom, the court found.

"[S]ometimes it is necessary to protect the superfluous in order to preserve the necessary," the majority concluded.