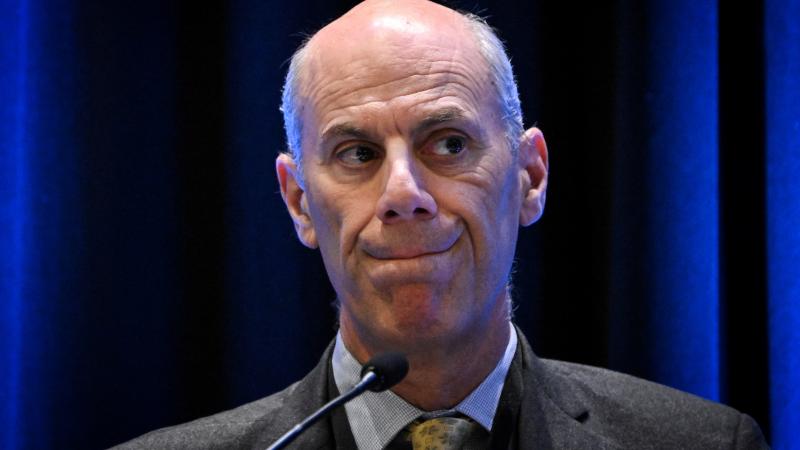

For black wealth expert Henry Childs, racial reconciliation starts with expanding economy

'You see these disturbances in America, because people when they feel like there's a lack of resources, then everybody tends to start fighting amongst each other,' says Henry Childs. 'So what we want to do is we want to create wealth.'

Part of what's driving racial unrest is America's failure to teach personal finance in schools, according to Henry Childs, the president of the Minority Wealth Commission.

In an interview with Just the News, Childs said his organization, which is devoted to growing wealth among disadvantaged minorities, is focused on improving education as a tool to help families break the cycle of poverty.

"It should be a crime for anybody to graduate a high school and not to have some foundational financial literacy," Childs said. "Because in a capitalist society, if you're not able to understand finance and able to leverage finance to better yourself, your family, your community, then you're going to be in a lot of struggle in life."

Childs was critical of the public education system's limited requirements in economics and personal finance. For example, the Council for Economic Education, which releases a biannual report examining states' curriculum requirements, reported in 2020 that just 23 states required public high school students to take a course in economics and just 6 states required high school students to take a course in personal finance. The study also found that just 10 states required public school standardized testing of economic concepts, and just 5 required the testing of personal finance concepts.

"I can honestly say to you, I don't really know what I got out of public education," Childs said. "I had to self-learn finance. I had to self-learn things like how to job hunt, how to market, how to get into sales."

Childs said the protests and turmoil sweeping America this summer — triggered by the death of African-American George Floyd while in police custody — were driven in part because of minority communities being left behind in a digital economy.

"I also think that schools should take a hard look at being more tech-savvy," Childs said. "As you saw, during the shutdown, schools were having a hard time doing basic things like making sure students showed up to class. This is the United States of America, and we haven't figured out how to do some type of education online. Until we start addressing those type of issues, we know this fourth industrial revolution, where everything is going digital, if we don't help our schools modernize and embrace this technology, we're doing our young generation a tremendous disservice. And some of these other countries are going to start, hopefully, not overtake us, but they're going to start nipping at our heels. So education, especially leaning into digital transformation ... has to be a part of K through 12 education."

Childs said the demographic change underpinning America's social unrest "is the biggest megatrend that there's very little attention on" and must be resolved heading into the future. Childs noted that among Americans under age 18, minorities now outnumber whites. He said that beginning in the year 2033, the minority working population in their prime years will exceed that of their white counterparts.

"But the problem is that this population growth is not coupled with economic growth, especially with wealth," Childs said. "We know that black and Hispanic families have less than 15% of the wealth as white families. So what we're trying to do with this commission is we know that if we can close the racial equity gap, it's going to be an $8 trillion gain in U.S. GDP."

Childs said the message from some Black Lives Matter protesters isn't expressing the right outrage: Protesters should be focused on growing the economic pie rather than expressing anger about how a pie is cut, which causes social divisions.

"I don't believe in slicing the pie," Childs said. "I'm a huge believer in getting the recipe so you can make your own pies ... So we don't want to pit white people against minorities. We don't want to pit corporations against workers. We want to say we're all in this together."

No stranger to systemic analysis, Childs served until this month as national director of the U.S. Department of Commerce's Minority Business Development Agency. He also co-led the White House Urban Revitalization plan under President Trump.

"We do work on social justice issues, but a lot of these are socio-economic issues," Childs said. "And that's why we want to focus on wealth. You see these disturbances in America, because people when they feel like there's a lack of resources, then everybody tends to start fighting amongst each other. So what we want to do is we want to create wealth, we want to actually build stuff."

Childs said his vision for the commission was to focus on three strategic areas: to create a wealth fund that invests in minority businesses, to expand venture capital and private equity investments in minority businesses, and to increase the role of minorities within the asset management industry.

"We know that until we can diversify the assets under management, we're not going to really be able to deploy money into the communities that we know need it the most," Childs said.

The Minority Wealth Commission partners with Fortune 100 companies, state and local government, and ethnic chambers of commerce, along with the National Urban League and other community-focused non-profits.

"We work with just about everybody who seriously wants to address, How do we close the racial wealth gap? How do we close the skills gap? And how do we close the digital divide?" Childs said.

For Childs, the way to promote racial reconciliation is clear: "You stop acting like resources are scarce, and you start creating a new economy."

Listen to the full interview with Henry Childs below: