Snapchat Holocaust joke tests SCOTUS protection for off-campus student speech

ACLU, Cato Institute, Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, Electronic Frontier Foundation defend student Snapchat post at 10th Circuit.

The Supreme Court protected the First Amendment rights of students outside of school and on social media this summer, and free speech groups want to ensure the precedent sticks in the federal appeals courts.

They are urging the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to side with a Colorado high school student who was expelled for posting an offensive Snapchat meme that drew a police visit but no arrest.

Unlike the cheerleader whose weekend Snapchat rant against her school SCOTUS deemed protected in the Mahanoy precedent, "C.G." didn't allude to Cherry Creek High School or any person in his 2019 post.

"Me and the boys bout to exterminate the Jews," he captioned a photo of friends in a thrift store wearing hats and wigs, including a "foreign military hat from the World War II period," according to a ruling last year dismissing his lawsuit against the school.

The caption riffed on a meme that was popular at the time. One of C.G.'s classmates saw the image and shared it with her father, who sent it around the local Jewish community. It made global Jewish news.

Though C.G. apologized for and removed the photo hours after posting it, Principal Ryan Silva suspended him for five days to investigate how the post "impacted the school environment" and another 16 days for an "expulsion review process."

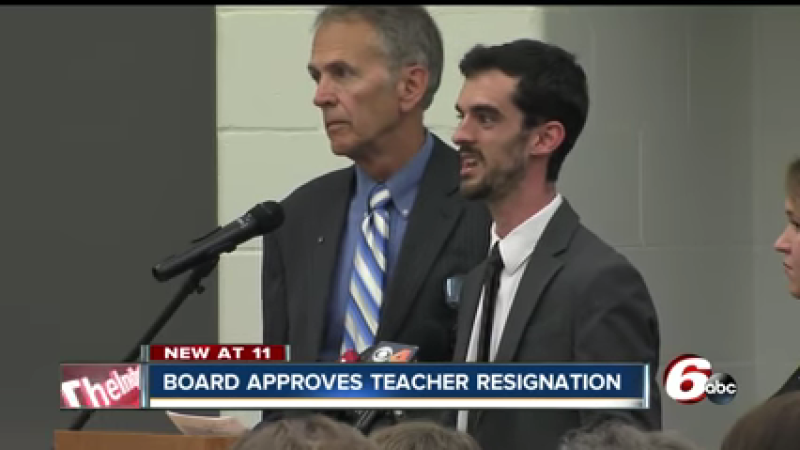

The policy he allegedly violated doesn't mention speech outside of school contexts, and he wasn't allowed to appeal either suspension. While a hearing officer dismissed the charge, Superintendent Scott Siegfried overruled the decision and also deemed C.G.'s speech "detrimental to the welfare or safety" of students and employees, creating a "threat of physical harm."

A federal judge determined that because "off-campus electronic speech regularly finds its way into schools and can disrupt the learning environment," the school can punish such speech under the Supreme Court's Vietnam-era Tinker precedent on in-school speech. The ruling came several months before Mahanoy.

The Cato Institute and Foundation for Individual Rights in Education warned the appeals court that this ruling, left unchecked, "could resonate on campuses across the country for years to come" because courts "often misapply K–12 precedent" to college students.

It would also mean "students would rationally but mistakenly conclude that they must self-censor everywhere, lest they cause offense to others," the civil liberties groups wrote in a friend-of-the-court brief. "The First Amendment does not permit such a panopticon."

Comparing C.G.'s suspension and overturned hearing to Lewis Carroll's "Through the Looking Glass," they said the Mahanoy precedent simply confirms the 1998 ruling that first upheld a student's offensive comments about his school on his website.

Courts have also shielded students from punishment over a "crude profile of a middle school principal" and a joke about making out with a teacher, the brief said, noting Justice Samuel Alito voted in favor of protections for offensive student speech years before he joined SCOTUS.

Because Tinker requires a "concrete threat of substantial disruption to the school" rather than the anticipation of "unpleasantness or discomfort," the district court misapplied the precedent, the brief said. It's not enough for a Snapchat post to cause "some isolated commotion in the community."

The school also violated the student's due process rights by failing to give him "sufficient notice of the charges he faced and a meaningful opportunity to contest them," accusing him of violating one policy and then expelling him on the basis of others, the brief said.

The district court ignored C.G.'s due process rights in the face of expulsion as well, by construing a lengthy meeting with the dean as a "hearing," the groups argued.

"Student expression online is not so different from other student speech away from school — such as at a protest, in an op-ed, or in a private conversation — to justify school officials' authority over it," the Electronic Frontier Foundation told the 10th Circuit.

The digital rights group, which also filed a brief in a pending 1st Circuit case on alleged bullying on Snapchat, argued that every approved intrusion of administrators into student speech falls within "narrow categories" on campus or school-supervised activities, including the "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" ruling.

Even though the Mahanoy ruling didn't set bright lines, it left out offensive speech from categories in which schools have a significant regulatory interest, particularly targeted bullying and "threats aimed at teachers or other students," the brief said.

The ACLU, whose lawyers represented the plaintiffs in both Mahanoy and Tinker, emphasized it was neither condoning C.G.'s "ignorant and asinine" speech nor arguing that schools can't use such speech for teachable moments, as Cherry Creek High School did.

But the student's speech was posted off-campus, outside school hours, "not targeted at any particular individuals," deemed nonthreatening by police, and "promptly removed and apologized for," the group said in its brief.

Each factor is relevant to an "overall assessment" that C.G.'s Snapchat post wasn't harassing — something the school didn't even argue, instead claiming "disruption" under Tinker.

The public has "a strong interest in hearing not only what adults have to say, but also the views of children," the ACLU said. "Young people are often at the forefront of movements, trends, and technologies, including through off-campus speech" online and protests in person.

The brief cited popular progressive causes to make its case that the Tinker standard should not be expanded off campus.

Parents should not have to worry that bringing their children to a Black Lives Matter march could give the principal an excuse to deem their participation "potentially disruptive," the ACLU said. Students should similarly not fear punishment for exposing their school's COVID-19 failures, such as sharing video of "crowded hallways."