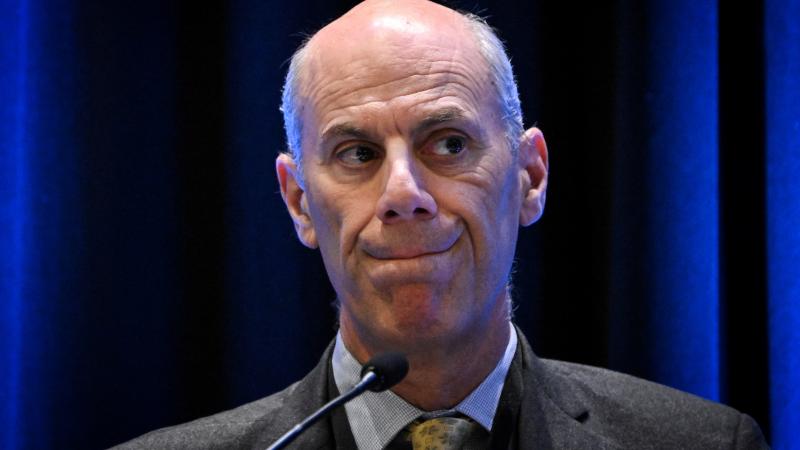

Architect of COVID-19 lockdowns resigns after flouting social distancing rules

British epidemiologist Neil Ferguson's predictions of 550,000 coronavirus deaths in the U.K. and 2.2 million in the U.S. led to highly restrictive stay-at-home rules in both countries.

Dr. Neil Ferguson, director of the prestigious MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis at Imperial College London, published an explosive report on March 16 predicting that without intervention coronavirus deaths in the U.K. could reach 550,000 and American fatalities could be as high as 2.2 million.

Alarmed by Dr. Ferguson’s predictions, the British government scrapped its original plan of allowing its population to acquire "herd immunity" to the virus naturally in favor of a strict lockdown. The U.S. government fell into line with similar guidelines shortly thereafter.

On Monday, the epidemiologist whose projections guided the imposition of strict stay-home measures resigned his position when it was reported that his married lover visited him at his home — twice — in defiance of social distancing rules.

Ferguson issued a statement accepting blame. "I accept I made an error of judgement and took the wrong course of action," he said. "... I deeply regret any undermining of the clear messages around the continued need for social distancing."

Ferguson had been recovering after having himself contracted the very virus he had been modeling, but he claims he was no longer infectious.

The day after release of the Imperial College report, the New York Times wrote, “With ties to the World Health Organization and a team of 50 scientists led by a prominent epidemiologist, Neil Ferguson, Imperial is treated as a sort of gold standard, its mathematical models feeding directly into government policies.”

Ferguson’s department is staffed with 200 researchers, but it turned out that his COVID-19 predictions relied on an old model he first created to plot the spread of an influenza outbreak in Thailand back in 2005.

Within a week of his report’s release, questions were being asked about Ferguson’s methodology. His response only rang more alarm bells: “I wrote the code (thousands of lines of undocumented C) 13+ years ago to model flu pandemics.”

Ferguson then claimed he was unable to publish his model until Microsoft began helping him sort out his code, in the last days before Bill Gates stepped down from the software giant’s board.

So far, all that has been published, according to Breitbart’s James Delingpole, is a reconstruction by Github, rather than the original source code, which raises troubling questions about its initial accuracy.

Computer predictions are only as good as the data they are fed, combined with their ability to account for all the variables involved. Ferguson’s influential COVID-19 model was driven by little more than very unreliable numbers coming out of China, plus the early figures from South Korea, Italy, and Spain. He seasoned his proprietary mix with numbers from the “Spanish Flu” pandemic after World War I.

Using his 15-year-old code, Ferguson concluded, “Based on our estimates and other teams’, there’s really no option but to follow in China’s footsteps and suppress.”

Ferguson has a history of vastly overestimating projected death tolls.

During the 2001 outbreak of foot and mouth disease among cattle and sheep in the U.K., six million animals were slaughtered as a precaution after Ferguson warned the government that 150,000 people could die. As it turned out, only 200 died.

A few years later, during the 2005 bird flu epidemic, Ferguson warned millions could die, but the actual figure was in the hundreds.

Uncertainty is inherent in any computer modeling. For a range of reasons both good (better safe than sorry) and bad (extreme predictions of death and destruction attract more media attention than more sober forecasts), modelers often opt to overestimate rather than underestimate dangers.

As Ferguson put it in February, according to Business Insider, "I much prefer to be accused of overreacting than under-reacting."

Ferguson wasn’t alone in his stark warning about COVID-19. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), based at the University of Washington in Seattle published a comparably influential, albeit less alarmist, report in late March.

Both IHME and Imperial are recipients of huge levels of funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. One of IHME’s board members is Dr. Sally Davies, who until last year was the Chief Medical Officer for England. She also has a long association with Imperial College and the WHO.

Gates’ view is that the coronavirus crisis can only be resolved through a vaccine.

When pressed on how far off a vaccine is, Gates told the BBC, “Governments will have to decide if they will indemnify the companies and really go out with this, when we just don’t have the time to do what we normally do.”

Unlike America, pharmaceutical companies elsewhere can be sued for the harmful side effects of vaccines. Gates feels that waiving that threat, together with many of the lengthy medical procedures involved in vaccine testing, is now justified in order to get vaccines out sooner.

But using a vaccine that hasn’t undergone full, rigorous testing, risks harmful, even fatal, consequences. Is it legally possible to force people to take a vaccine that has not been fully tested?

Sweden chose a very different path, and its decision not to go into lockdown has drawn criticism from President Trump, among others.

“Despite reports to the contrary, Sweden is paying heavily for its decision not to lockdown,” Trump tweeted. He cited its fatality levels of around 2,500, compared to lower totals for its Scandinavian neighbours Norway (207), Finland (206), and Denmark (443), as of April 30.

Doubters notwithstanding, Swedish Ambassador to the U.S. Karin Ulrika Olofsdotter claims her country could reach herd immunity” to the virus within weeks — at least in the densely populated area around Stockholm.

The justification for adopting more restrictive measures elsewhere was to “flatten the curve” of infections and prevent health services being overwhelmed; yet even in Sweden that didn’t happen, and its healthcare system has coped so far.

Swedish epidemiologist Andrew Tegnell offered CNBC a very practical reason for their approach: “Once you get into a lockdown, it’s difficult to get out of it. How do you reopen? When?”

The Swedish alternative is risky, but as of May 4, according to Worldometer, its total of 2,769 deaths in a population of just over 10 million is still only around two thirds as high, proportionately, as the U.K.’s total of 28,446 fatalities out of its population of 67 million, even though it is under lockdown.

Add to that the U.K., unlike Sweden, will likely have to face a new infection wave once Dr. Ferguson’s measures are relaxed. So too will America.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Links

- Imperial College March 16 report

- The Telegraph: How architect of lockdown was brought down

- New York Times: Virus report that jarred US, UK to action

- Wall Street Journal: Coronavirus lessons

- Breitbart: Coronavirus decision makers clouded in secrecy

- LiveScience on coronavirus death toll projections

- Bill Gates on BBC

- Trump tweet on Sweden

- NPR: Swedish ambassador on herd immunity

- Business Insider: architect of Sweden's lax coronavirus policy

- CNBC: Stockholm expected to reach herd immunity

- Worldometer