New research suggests asymptomatic COVID-19 spread is comparatively rare

Asymptomatic cases are "least likely to infect their close contacts," study finds.

New research out of China suggests that the level of asymptomatic spread of COVID-19 may be less of a threat than is currently widely believed, findings that could influence mitigation measures such as social distancing rules and mask mandates.

Much of the rationale for the coronavirus lockdown policies and countermeasures undertaken by governments across the world over the past several months has been based on the assumption that the virus spreads easily among people showing no symptoms. Scientists have feared that many individuals may transmit the disease via saliva droplets without feeling ill or showing any outward signs of infection, rendering containment of the virus much more difficult.

Medical authorities across the world have since late last year been scrambling to determine just how prevalent asymptomatic spread of the virus truly is. Research into that question is as still sparse but ongoing.

Asymptomatic cases "not the major drivers" of pandemic, scientists claim

Earlier this month, a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine announced findings that asymptomatic patients were, in both relative and absolute terms, unlikely to infect close contacts.

The researchers, based largely out of Southern Medical University in Guangzhou, China, tracked the level of "secondary attack rate" among COVID-19 patients of varying degrees of infection. A secondary attack rate is the level at which a disease is transmitted among close contacts in familiar settings.

"Patients with more clinically severe disease were more likely to infect their close contacts than were less severe index cases," the researchers found; they added that "asymptomatic cases were least likely to infect their close contacts."

The scientists said they discovered that "the risk for transmission via public transportation or healthcare settings was low," particularly in comparison to household settings. One explanation they advanced was that "mask wearing to prevent infection was mandatory in public settings but not in households during the study period."

Overall, the paper claims, "patients with COVID-19 who had more severe symptoms had a higher transmission capacity, whereas transmission capacity from asymptomatic cases was limited."

"This supports the view of the World Health Organization that asymptomatic cases were not the major drivers of the overall epidemic dynamics," the researchers added, citing a February WHO report which asserted that asymptomatic spread "does not appear to be a major driver of transmission."

Opinions on asymptomatic spread have varied considerably

Though significant asymptomatic spread of COVID-19 has been assumed by many scientists and governments around the world since the start of the year, evidence for its widespread occurrence remains relatively elusive.

Governments have instituted measures such as lockdowns, social distancing policies, mask mandates and other rules under the assumption that unmasked individuals in close proximity to one another may be spreading COVID-19 without even being aware that they are infected with it.

Yet in June, World Health Organization infectious disease expert Maria Van Kerkhove said in a press conference that asymptomatic spread of the disease "appears to be rare." Those remarks set off a flurry of controversy, leading Van Kerkhove to state a day later that asymptomatic spread was still "a big open question," though she did not retract her earlier claim that it was "rare."

Major public health officials such as the Dr. Anthony Fauci have known about the possibility for COVID-19 spreading asymptomatically since at least late January of this year, though it wasn't until early April that Fauci and other U.S. officials began publicly advocating the broad usage of face coverings throughout society, a measure considered one of the key methods to counteract asymptomatic transmission.

The possibility of asymptomatic spread has also been a significant driver in the calls for increased testing, with advocates claiming that potentially infected individuals should be tested in order to avoid the possibility of infecting others without showing symptoms.

That assertion came to the forefront of the U.S. coronavirus debate this week when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quietly revised its guidance on testing, stating that individuals who have come into contact with an infected person "do not necessarily need a test unless you are a vulnerable individual or your health care provider or State or local public health officials recommend you take one."

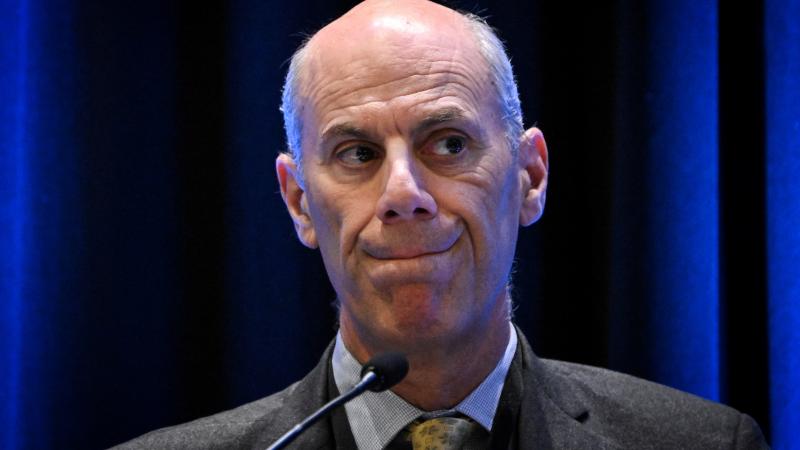

Following criticism of that new policy, CDC Director Robert Redfield clarified that "everyone who needs a COVID-19 test, can get a test," though the revised guidelines on the CDC's website remained the same.