As racial politics become more intense, Biden faces awkward questions over his past

A five-decade-long political career is running up against the era of Black Lives Matter.

"Now is the time for racial justice," Joe Biden declared in an address at George Floyd's recent funeral, signaling his acute awareness that racial issues have been thrust to the forefront of American politics for the foreseeable future.

Yet Biden's hopes of adapting his campaign to reflect and take advantage of the suddenly transformed racial politics of the moment are greatly complicated by a long record of public statements and legislative action not easily reconciled with the purist, Black Lives Matter-style approach to racial issues emphasizing systemic racism, white guilt, and police violence that has overtaken large segments of the Democratic Party in the last three weeks.

Nearly 50 years in politics have left the presumptive nominee with several racial albatrosses around his neck.

Confederate generals and a crime bill

The present Black Lives Matter zeitgeist has fixated significantly on the various Confederate statues that dot the American South, with activists calling for the monuments of rebel generals, soldiers, and politicians to come down; in many cases, rioters have destroyed the statues themselves rather than wait for municipal authorities to do it.

Yet Biden's own political track record contains two especially awkward votes: In 1975 he voted to posthumously restore the U.S. citizenship of the commander of the Confederate army Gen. Robert E. Lee, and in 1977, he voted to do the same for the Confederacy's president, Jefferson Davis.

Those votes may be unsurprising from the perspective of American political history: Until fairly recently, the Democratic Party was firmly the party of the South. Jeff Davis himself was a Mississippi Democrat in the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives.

Yet as late as 1987, Biden was still invoking a cultural affinity with the Old South when politically expedient: He told a group of Alabama supporters during his presidential bid that year that his state of Delaware was "on the South's side in the Civil War." The remark served as an awkward acknowledgement that, though Delaware did not secede with the South, it remained a slave state for the length of the war.

Nothing makes Biden more suspect to a new generation of racial activists than his authorship of the landmark 1994 crime bill. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 provided for 100,000 new police officers across the country, several billion dollars in funding for prisons, and multiple new federal statutes involving gang activity and prostitution. It also expanded the number of crimes under which the federal government could seek the death penalty.

At a time when "defund the police" is a trending slogan on the political left, Biden's crime bill may hinder his appeal among younger voters. Biden has conceded that questions about his support for that bill are "legitimate," though he has denied that it is hurting his chances with younger Americans.

"Watch what I do," Biden implored voters this week. "Judge me based on what I do, what I say and to whom I say it."

'You ain't black'

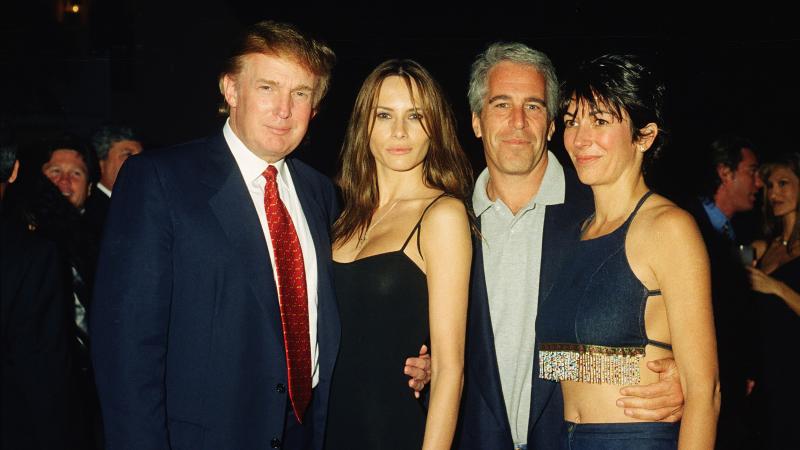

Biden's problems on race are not confined to decades-old votes or episodes of political pandering to Southern whites. Even his recent history is spotted with memorable gaffes that could cool enthusiasm for him among black voters, from whom he needs not just an overwhelming margin of support but also heavy turnout if he is to win in November.

In 2007, referring to his then-rival for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination Barack Obama, Biden described him as "the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy." The word "articulate" has long been a sensitive adjective among some black Americans, who claim it is often deployed by white people with low expectations of blacks. (Biden's remarks "drew scrutiny," as CNN put it at the time, though they ultimately did not dissuade Obama from choosing Biden as his running mate.)

Several years later, during the 2012 election, Biden appeared to insinuate that Mitt Romney would re-enslave black Americans, telling a crowd that contained hundreds of black supporters that the Republican candidate would "put ya'll back in chains." His remarks were derided as "stupid" by U.S. Rep. Charlie Rangel, while former Virginia Gov. Doug Wilder implied that Biden was separating himself from the black audience he was hoping to reach.

Just last month, Biden was roundly condemned by black leaders for telling black radio personality Charlamagne tha God that if you are African-American and thinking of voting for Trump, then "you ain't black." (Biden later apologized for that claim, calling it "cavalier.")

The Biden campaign did not respond to requests for comment on Friday regarding his uncomfortable racial record.

Biden's possible loss of black voters — and young, highly racially conscious voters of any race — would not necessarily translate to voter gains for Trump: It may be that disillusioned liberals simply stay home rather than vote for a Democrat with such a checkered political history. Still others may feel that they have been "taken for granted by the Democratic Party and Democratic philosophy" and might break for Trump, as one activist told Just the News recently.

Biden, of course, famously forged a lasting bond with black voters by serving for eight years as vice president under the nation's first black president. Will that residual respect and gratitude be enough to drive the black turnout Biden needs to win? The answer depends in part on the public's reaction to deeper scrutiny of his history on racial issues, a track record that hasn't aged well in today's uncompromising new racial climate of rage, suspicion, intolerance, and hair-trigger sensitivities.