Moral of Sussmann trial: Americans see lying as a DC norm, making punishment hard

"There are bigger things that affect the nation than a possible lie to the FBI," jury forewoman declares after verdict.

Over the last four years, Special Counsel John Durham has built a compelling case, supported by evidence, that the entire Russia collusion narrative that gripped the country during Donald Trump's presidency was built on falsehoods.

An FBI lawyer, after all, has admitted he misled the FISA court by falsifying a document. Hillary Clinton's campaign and the Democratic Party has paid a fine to federal election regulators for falsely disguising payments for Christopher Steele's dossier as legal work rather than opposition research.

Steele's primary source, Igor Danchenko, is charged with lying to the FBI. And before he was indicted, Danchenko told the FBI that Steele misrepresented some of his contributions to the dossier as intelligence when in fact they were based on "just talk" and "hearsay" and "conversation ... with friends over beers."

Clinton campaign manager Robby Mook testified Hillary Clinton personally approved releasing Russia dirt on Trump in 2016 even though they weren't sure it was true.

And FBI supervisors who handled Clinton campaign lawyer Michael Sussmann's allegation of a secret Trump communications channel with the Kremlin misled their own agents, falsely claiming the evidence came from the Justice Department when instead it came from a private lawyer.

So when Durham asked a Washington, D.C. jury to convict Sussmann for an alleged lie, he again offered strong evidence.

Documents presented to jurors showed Sussmann texted the FBI's top lawyer he was bringing the allegations of the secret Alfa Bank communication channel to the bureau as a private citizen. But in fact he charged the work to the Clinton campaign.

And in later testimony to Congress, Sussmann gave a different story, claiming he did in fact approach the FBI on behalf of a client. One of the two statements could not be true, prosecutors argued.

In the end, it didn't matter. The case was made against a backdrop of so many prior falsehoods and a growing belief in America that lying has become a norm in politics in Washington.

The forewoman for the jury that acquitted Sussmann said as much in a brief statement to the news media Tuesday afternoon, suggesting it wasn't worth the jurors' time to convict someone for lying to the FBI.

"I don't think it should have been prosecuted," the jury forewomen said, according to an account in The Washington Times. "There are bigger things that affect the nation than a possible lie to the FBI."

Such sentiments were predicted in polling two years ago, just before Donald Trump was beaten by Joe Biden in an election where a lie — that Hunter Biden's laptop was Russian disinformation — clearly impacted voters.

A Newsweek poll in late October 2020 found that a stunning 54% of Americans agreed with the statement that lying has become more acceptable in American politics. In other words, it is no big deal.

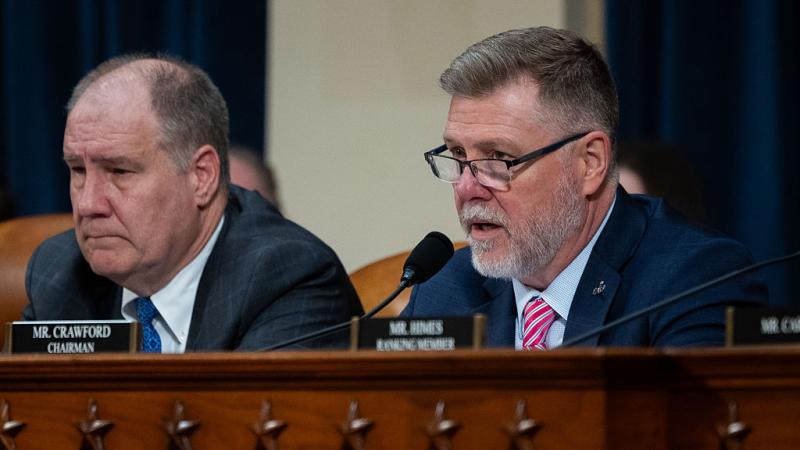

Kevin Brock, the FBI's retired intelligence chief who monitored the Sussmann trial closely, told Just the News that the evidence submitted by Durham during the trial that the FBI was lying to its own agents likely had a profound impact on the jurors.

"The Durham prosecution team introduced an FBI communication that indicated that the FBI itself was misleading the agents who were charged with conducting the Alfa Bank investigation by saying that the information came from Department of Justice and not a third party, namely, Michael Sussman," Brock told the "Just the News, Not Noise" television show Tuesday night.

"We can only read into that," Brock continued, "that there were efforts at FBI Headquarters to conceal that from the investigators so that they wouldn't ask the questions and maybe conduct a less complete investigation because they're thinking this information came from a political campaign.

"There's a hidden agenda there. So I think that that piece of information was certainly something that the jury took into consideration. If the FBI is going to be misleading in this regard, or at least individuals at FBI Headquarters can be misleading, then how can they convict Michael Sussmann?"

He added: "A finding of not guilty doesn't mean he didn't mislead the FBI. I think the evidence showed that there was some intent, some duplicitous attempt of intent there. But the jury had plenty of plenty of room to find him not guilty in this charge."

Brock said Durham appeared to use the trial to tell a larger story about how the Clinton campaign used the FBI to carry out a dirty trick.

"I don't think he is going to lose any sleep over the fact that Michael Sussman was acquitted," he said. "The trial afforded him an opportunity to paint a picture about an effort by the Clinton campaign to spread disinformation on two tracks: No. 1 the Alfa Bank narrative, and No. 2 the Steele dossier. And that was intentional."

Durham will get the chance to explore the problems with the Steele dossier in greater deal in October when Danchenko's trial begins.

In the meantime, the Sussmann verdict will give both sides ammunition for their echo chambers.

Sussmann himself crowed the verdict showed he had told the truth to the FBI and was wrongly prosecuted, a line Democrats will use to bludgeon Durham going forward. Sussmann's own lawyer, Sean Berkowitz, reviewed that argument in his close to the jury.

"Opposition research is not illegal," he argued. If it were, "the jails of Washington, D.C., would be teeming over," he added.

Conservatives, meanwhile, will see the verdict as further confirmation of a dual justice system that prosecuted former Trump National Security Advisor Mike Flynn for lying but allowed Sussmann and former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe to escape punishment despite allegations of lying.