PETA and Project Veritas agree? Mainstream media absent from challenge to ban on public recording

Full 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals threw out panel ruling that struck down Oregon law that bans "unannounced" audio recording of politicians - but not police - in public. Animal rights, free speech groups side with Project Veritas.

Is it worth crippling freedom of the press, from conservative stings and factory-farming exposes to citizen journalism and local watchdogs, to hide the public conversations of politicians?

That's one framing of the issue confronting the full 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals as the 29-member court, minus two unexplained recusals, reviews the constitutionality of an Oregon law that prohibits "unannounced audiovisual recording" in public – unless the speaker being recorded is an on-duty cop, or a "felony that endangers human life" is taking place.

A majority of non-recused judges voted in March to overturn a divided three-judge panel that knocked down the statute last year as a content-based restriction that is "not narrowly tailored to achieving a compelling governmental interest," failing the high judicial bar of "strict scrutiny."

The panel majority specifically faulted the law for privileging "a state executive officer’s official activities" over "a police officer’s official activities," while the dissent argued the law would be content-neutral if the panel let the Beaver State sever the exceptions. The state didn't seek that, and the majority said a general ban would create "significant constitutional issues."

Short supplemental briefs are due Tuesday to address two specific questions as well as "any other properly raised issue concerning the merits," the full court said May 13.

The first is whether the section of the law that prohibits obtaining or trying to obtain "any part of a conversation by means of any device, contrivance, machine or apparatus," unless "all participants are specifically informed" what's happening, "triggers First Amendment scrutiny" – in other words, any First Amendment relevance to a ban on audio recording.

The second is whether the law's exceptions constitute content-based speech regulations, which would trigger strict scrutiny.

That would likely doom the statute unless Oregon can show it has a compelling interest in the privacy of public conversations and the law is the least restrictive way to protect that privacy, attorney Gabe Walters of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, which filed a joint friend-of-the-court brief last month, wrote in an email.

"The government will be unlikely to carry that burden because, for example, a party to a conversation could roughly transcribe it from memory immediately afterward without the consent of the other parties to the conversation," Walters said.

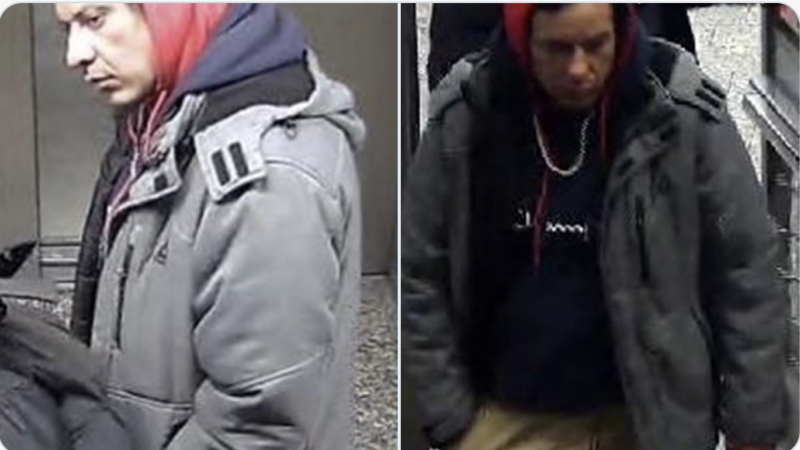

The case has drawn surprisingly little interest beyond plaintiff Project Veritas, whose bread-and-butter is unannounced audiovisual recording, and defendant Oregon. (Project Veritas parted ways with its founder James O'Keefe two months after oral argument.)

Not one mainstream media organization or press freedom group filed friend-of-the-court briefs, nor the ACLU, according to the docket going back to the 9th Circuit's original agreement to review U.S. District Judge Michael Mosman's 2021 ruling upholding Oregon's law.

The ACLU did express concerns about the FBI raiding O'Keefe's home in 2021 in connection with the diary of President Biden's daughter Ashley, which Project Veritas said it obtained legally during the 2020 campaign but tried to return to law enforcement.

The only outside brief submitted before the panel ruled came from Portland lawyer Bert Krages, whose legal handbook for photographers came out shortly before the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. He became a louder activist for photographers' rights in public amid post-attack crackdowns by "overzealous law enforcement officers, security guards" and others.

Krages filed again in April, saying the law personally restricts his ability to advocate for environmental restrictions on "wakesurfing" because he makes videos in public that unavoidably contain "conversations that are extraneous to the subject matter I am trying to record."

For example, he was once recording on the Willamette River "when an unseen person on the other side began using a bullhorn to communicate to unseen listeners." The law functionally shuts down recording wherever "a multitude of conversations are taking place."

The law isn't even limited to "face-to-face conversations," Krages told the full court, requiring that "the person making the recording must inform any silent listeners to a conversation as well as those who speak."

He said it was "often impossible and sometimes ill-advised" to announce when recording "hate speech, criminal activity, [or] child abuse," and the full court can't save the overbroad law simply by assuming "prosecutorial discretion will be exercised."

The conservative Liberty Justice Center urged the full court to takes its cues from Supreme Court decisions on sign codes in 2015 and 2022, striking down one that "treated ideological signs more favorably than political signs" and upholding the other while clarifying that "swapping an obvious subject-matter distinction for a 'function or purpose' proxy" has the same problem.

The public interest law firm rattled off a long list of specific situations in which the law doesn't apply to illustrate how thoroughly content-based it is, showing the law is not a permissible "time, place, or manner restriction."

FIRE's joint brief is signed by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, which has a "long history of conducting undercover investigations to expose cruelty to animals," and Animal Outlook, which shares undercover agribusiness recordings with "law enforcement officials so they have proof of crimes against animals."

University of Denver law professors Alan Chen and Justin Marceau, who wrote a "monograph studying the historical role of undercover investigations in promoting democracy," also signed. They received PETA "Justice for Animal" awards for assisting a legal challenge to Idaho's so-called ag-gag law in 2018.

"The gathering and dissemination of information about matters of public concern is no longer exclusively or even primarily the province of a small number of newspapers, journalists, or authors," they wrote.

What's at stake is nothing less than the continued viability of the "citizen-journalist," whose interest is at the heart of the founders' conception of freedom of the press and whose work has never been less expensive to produce and find an audience, their brief says.

The Supreme Court ruled conclusively that "audiovisual recording is speech," according to the groups, when in 2011 it struck down a Vermont law that prohibited pharmacies from disclosing and pharmaceutical companies from using "prescriber-identifying information for marketing purposes without a doctor’s consent."

The state allowed use of the information for medical research and its own "prescription drug education program," however.

The 6-3 ruling confirmed that governments cannot regulate speech based on its content "even if the speech is commercial in nature," as then-Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote.

He quoted from its 1996 ruling that prohibits states from enacting "total bans on truthful commercial advertisements," which said the First Amendment "directs us to be especially skeptical of regulations that seek to keep people in the dark for what the government perceives to be their own good."

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press backed the healthcare services provider challenging the law in a friend-of-the-court brief, citing the law's negative implications for "data gathering, analysis and publication … in journalism today."

The new instructions from the full court May 13 suggest it may revise a divided panel's precedent from the 2018 ruling against portions of Idaho's ag-gag law, which the Animal Legal Defense Fund challenged.

The Legislature passed the law following outrage about a "secretly-filmed exposé of the operation of an Idaho dairy farm" that went viral for its "disturbing" depiction of how cows were treated, but it impermissibly criminalized "misrepresentations to enter a production facility" and prohibited "audio and video recordings of a production facility’s operations," the court found.

The panel determined, however, that it permissibly criminalized "obtaining records … by misrepresentation" and "employment by misrepresentation with the intent to cause economic or other injury."

RCFP, American Society of News Editors, Wall Street Journal publisher Dow Jones, broadcasting giant E.W. Scripps, Society of Professional Journalists and many other media organizations and associations backed ALDF in a joint brief at the time.

The Facts Inside Our Reporter's Notebook

Videos

Links

- divided three-judge panel that knocked down the statute

- (Project Veritas parted ways with its founder James O'Keefe

- Judge Michael Mosman's 2021 ruling

- ACLU did express concerns about the FBI raiding O'Keefe's

- Bert Krages, whose legal handbook for photographers

- Krages filed again in April

- Liberty Justice Center

- FIRE's joint brief

- "monograph studying the historical role

- PETA "Justice for Animal" awards

- 2011 it struck down a Vermont law

- 1996 ruling that prohibits states from enacting

- Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press backed

- 2018 ruling against portions of Idaho's ag-gag law

- backed ALDF in a joint brief