NIH accidentally unmasks official who hid Chinese-submitted coronavirus data in March 2020

Agency asks court to seal records related to FOIA lawsuit that name NIH "curator" who approved removal request and Chinese researcher who submitted it. Whistleblower support activist says names were publicly available to researchers, not "classified information."

The National Institutes of Health deleted two "sequencing runs" of pangolin coronavirus from its National Library of Medicine (NLM) at a Chinese researcher's request on the eve of U.S. COVID-19 lockdowns, months before a previously known removal requested by a different Chinese researcher, according to newly disclosed records.

Now the agency is trying to convince a federal court to seal portions of those records and a litigant's filing that name the earlier Chinese researcher and his NIH handler, claiming it "inadvertently failed" to redact them in responding to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit.

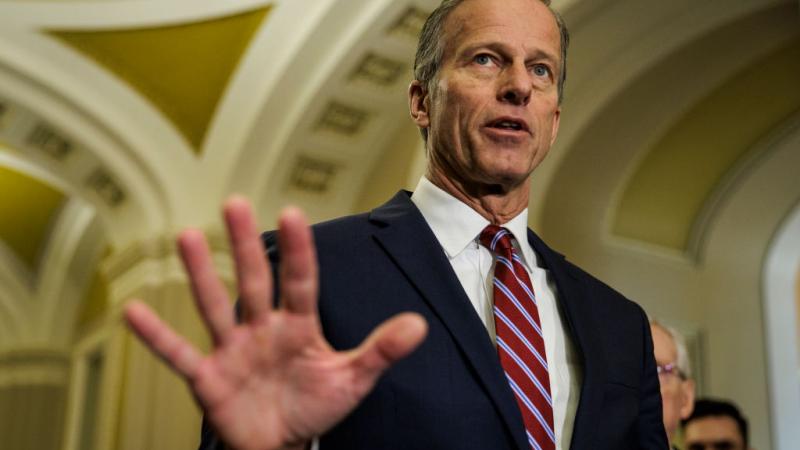

The government is trying to "put the toothpaste back in the tube," said Empower Oversight founder Jason Foster, whose whistleblower support group filed the lawsuit last fall.

The former Senate Judiciary Committee investigator told the John Solomon Reports podcast the feds are suddenly "moving heaven and earth" when it comes to the privacy of a researcher "associated with the Chinese government" and information that could shed light on "the origins of the pandemic."

This is "a huge contrast to what we see them doing" with U.S. government whistleblowers, including a case he's working on, Foster said.

The first emails obtained by Empower in the lawsuit showed an NIH staffer agreeing to remove a genetic sequence from public view in June 2020 upon the request of a Wuhan University researcher and asking for clarification on whether to remove another sequence. Both names were redacted.

The new batch of emails show NIH staffers deliberating how to respond to questions last fall from Jesse Bloom, who runs a virus and protein evolution lab at Seattle's Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center.

His preprint paper on NIH's sequence removal at the Wuhan researcher's request prompted a tense meeting months earlier with scientists, including then-NIH Director Francis Collins and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Anthonyo Fauci. Bloom recounted both officials saying they weren't asking him to withdraw the paper from public view.

"I'm writing to inquire about some more deleted deep sequencing runs from China on the SRA," Bloom wrote Oct. 12 to Steve Sherry, acting director of NLM's National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), which hosts the Sequence Read Archive.

He noticed "curator" Rick Lapoint deleted the two pangolin coronavirus sequences March 16, 2020 at the request of the Chinese scientist who submitted them, Kangpeng Xiao of South China Agricultural University, "under the stated rationale that they were accidental uploads unrelated to the project."

What puzzled Bloom was that the sequences "re-appeared on the SRA over a year later," he said. At that point an unidentified "investigative entity" asked NLM and NIH for "all correspondence related to these accessions" March 2020-June 2021. (Bloom later clarified the entity was not the FBI and told Just the News it was nongovernmental.)

Their document dump "did not indicate any further correspondence" regarding the two samples after March 2020, Bloom told Sherry. Since NIH has previously said removed sequences are "only restored if the submitter requests that," he asked whether the feds left out the Chinese university's request or NCBI restored them without a request, and the "rationale and process" if the latter.

NIH news media chief Amanda Fine forwarded Bloom's questions to NIH officials, including Collins and Principal Deputy Director Lawrence Tabak. She shared the proposed response written by NLM, which is redacted.

Her email is dated Nov. 16, more than a month after Bloom's. Fine didn't answer Just the News queries, including why the proposed response took so long. No further responses are recorded in the documents posted by Foster's group.

NIH filed a motion for summary judgment last month, claiming it had fulfilled Empower's FOIA requests but also invoking an exemption from disclosure "because of the amount of misinformation surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic and its origin.”

Empower responded July 11 by noting media reporting that while only 0.19% of 2.4 million SRA submissions of DNA sequencing data had been withdrawn from March 2020-March 2021, more than 200 entries for "early COVID-19 cases" were removed in summer 2020.

It said the agency violated FOIA by first responding "months too late" to both its requests, hiding responsive records that are not "deliberative" because they lack "give-and-take consultation," and failing to conduct "searches reasonably calculated to lead to responsive records."

NIH's FOIA production included references to previous communication with Bloom and a "last set" of questions and answers regarding the Wuhan University sequences, neither of which were provided. The court also previously noted "almost all" the records NIH turned over in its "final" production in February came from a single "subagency," Empower said.

The agency misused an "unwarranted invasion of personal privacy" exception to hide the names of the curator and Chinese researcher associated with the June 2020 SRA removal, the group argued. It noted NIH didn't redact the curator and researcher from the March 2020 sequence removal even though its FOIA officer claims to have vetted the production.

The inclusion of the two names apparently caught NIH by surprise. It filed a motion to seal July 15, arguing there is "no public interest in learning these names" and that they could face "harassment or media scrutiny." The agency did not waive the privacy exemption through this "inadvertent disclosure."

Foster offered an alternate explanation to the John Solomon Reports podcast. The March 2020 revelation shows NIH made "multiple deletions" of "public information that Jesse Bloom had access to" and brought to the agency's attention, he said. "It's not some kind of private government information or classified information."

The irony of the Privacy Act is that "the government almost exclusively uses it not to protect you and me, but to protect themselves," Foster said.