Fired for quoting N-word, professor settles case too early to benefit from academic freedom ruling

Tim Boudreau riled his university for a decade by inviting controversial speakers. He fears "modern-day woke liberals" are taking over.

Tim Boudreau invited some of the most hated people in America — including the family behind anti-gay protests at military funerals — to address his media law classes at Central Michigan University (CMU) for more than a decade.

But it was his recitation of racial slurs from a court decision — against his employer, as it happens — that got the journalism department chair fired last fall.

After months of saber-rattling about a First Amendment lawsuit, Boudreau and the public university quietly reached a preventative settlement in February, disclosed this month through a public records request.

He received 10 months' salary and benefits from the date of his firing and agreed to retire. The university agreed to remove all references to its investigations and termination of Boudreau, who was tenured, from his file.

A month later, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals issued a far-reaching ruling in favor of academic freedom for faculty at public universities, even when they refuse to address transgender students by their preferred pronouns.

Boudreau had been waiting for the decision, which would apply to his situation, he told Just the News. It could have made a potential lawsuit against CMU a slam dunk, or at least compel the university to offer him a better settlement.

Now the former professor is reconsidering whether he should have gone to court after all.

CMU's initial offer was "really, really weak," but litigation was not appealing either, he said. The dispute had already caused "considerable stress" to his family, and he'd have to hold his tongue for at least two years if he sued.

Boudreau decided he could "live with" the second set of settlement terms, which importantly allows him to criticize his termination and defend "the efficacy of his teaching methods."

In a wide-ranging interview, Boudreau shared his thoughts on making students uncomfortable, how he'd escaped student complaints about his methods until last summer, and the declining ranks of faculty who are "more of a classic liberal" like him, rather than "a modern-day woke liberal."

He is adamant, however, that students are not the problem. "Very few have ever complained" out of the hundreds he's taught, he said. Instead, it's the administrators who are "deathly afraid" of dealing with outrage, especially on social media.

"These are highly paid professionals in their field, and you'd think they'd know" how to explain the value of academic freedom to "disgruntled" students, parents and alumni, Boudreau said.

The university "conducted a thorough investigation into this matter and stands by the outcomes of that investigation," and its settlement with the unnamed faculty member was "satisfactory for both parties," a spokesperson told Just the News.

Citing the privacy of "personnel issues," it declined to discuss the potential chilling effects on other faculty from Boudreau's investigation and how far it extends proscriptions on what faculty can say in the classroom.

The university's investigative report against Boudreau implies faculty could get in trouble for mentioning the Asian-American rock band The Slants.

Challenging students with a 'convenient allegiance to the First Amendment'

The journalism professor had been a burr in the side of CMU going back to President Obama's first term.

In 2010, he invited the family-run Westboro Baptist Church, infamous for its "God Hates Fags" activism, sparking student protests outside the locked and guarded classroom. The next year he invited Florida pastor Terry Jones, who would appear in Michigan court the next day to appeal a "breach of peace" conviction for burning the Koran.

Westboro Baptist members came back in 2018 alongside the head of the Detroit Satanic Temple. The university heavily restricted access to the event, banning media coverage for the first time since Boudreau started hosting controversial speakers.

Boudreau laughed about the university's rationale for the ban: to comply with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. Every time it tried to tamp down on publicity, he said, the university ended up drawing more attention to his classroom events.

The speakers were chosen not just to illustrate the material his classes covered, but also to confront students with the possibility that they had a "convenient allegiance to the First Amendment" for only popular speech.

He didn't mind if students grappled with these legal protections for offensive speech and concluded they went too far, and he gave them a set number of excused absences if they wanted to avoid certain speakers.

But it's especially important for journalists in training to be exposed to different viewpoints and treat those adherents in a civil manner, Boudreau said. Some of his gay students said they were "delighted" he invited Westboro Baptist so they could challenge the church members' views, as the professor intended.

Boudreau was "quite surprised" to have escaped formal student complaints over his subject matter and teaching methods for so many years, he said. He thinks he knows what changed the landscape last summer.

'Personal titillation,' not pedagogy

One day in class, the professor was going over a 6th Circuit ruling that invalidated CMU's speech code as unconstitutional.

The court upheld the university's firing of its basketball coach, however, for calling his players "niggers" in what the coach characterized as a "positive and reinforcing" manner. Written by a 70-year-old black judge, the 1993 opinion included 19 uses of the racial slur.

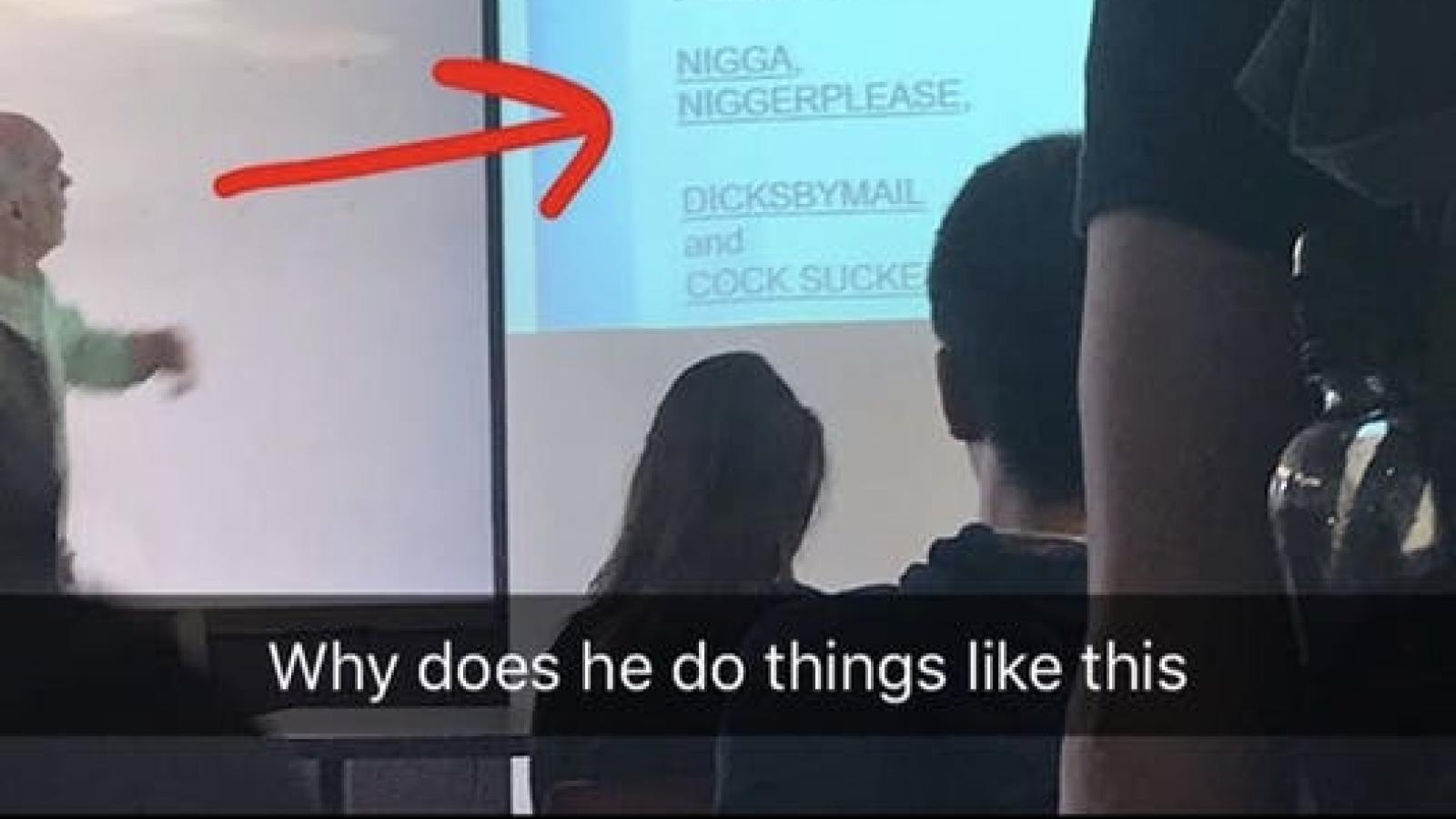

CMU quickly opened an investigation after a former student posted a video from 2018 that captured him reading slurs from the opinion. She also posted an image from Boudreau's presentation that shows uses of the N-word in trademark applications that followed a recent Supreme Court ruling against a law that banned "disparaging" marks.

According to the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, which represented Boudreau as he considered litigation, Provost Mary Schutten asked him to never use the N-word in any context again. He refused and was put on paid leave the same day.

An August investigative report faulted Boudreau for teaching the 6th Circuit precedent against CMU and the Supreme Court trademark ruling, judging them irrelevant to his class. He should have stuck with "primary precedents" related to campus speech codes, including a ruling against the University of Michigan that didn't involve racial slurs.

The university concluded that using "uncensored slurs" or "denigrative language" in the classroom was closer to "personal titillation" than legitimate pedagogy. Boudreau "indulged his own personal amusement in using the N-word" by teaching the two cases.

First Amendment law experts, including a former president of the ACLU, challenged the university's analysis in an October letter demanding the reversal of his termination. They highlighted the "slippery slope" in the investigative report, which also faulted Boudreau for quoting "homophobic slurs" from the Supreme Court ruling in favor of Westboro Baptist.

The ex-professor believes the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the protests that followed "are what really prompted [administrators] to overreact" to his classroom material, he told Just the News. "They wanted to suggest to the public that we wouldn't tolerate even a hint or a suggestion of racism, no matter how unfounded that claim might be."

Colleagues seem worryingly 'nonchalant'

The faculty union initially represented Boudreau. Before he could file suit, he had to go through arbitration and then wait up to two months for a decision.

Even if he prevailed, Boudreau wasn't guaranteed to keep his position as chair of the department, and returning to class would be his "reward," he said, using air quotes. He was also retirement age already.

Boudreau was also concerned the university would try to nail him again for classroom comments taken out of context, and that so many colleagues "seem nonchalant" or just spooked silent by his treatment, including those who also refer to uncensored slurs in their teaching.

"I think there will be a real chilling effect on faculty," he said. "At best they will be confused and uncertain, and at worst they'll remain silent and they won't take any chances whatsoever."

He's concerned this is already happening in journalism education. There's a growing number of academics who "tiptoe around the language" that they used to teach without blowback.

But he's still hoping to shape the perspectives of younger students. His nephew's wife invited Boudreau to address her high school journalism class, and he'd like to speak in K-12 settings more broadly.

Boudreau is also hoping for an invitation to speak again at CMU, including a debate on offensive language. He's persuadable, he insists.

"I'm not some loony" who will "die on that hill," he said.