Russia uses mercenaries to sow chaos in Libya, experts say

The Wagner Group private military company is fighting in Libya, and is an instrument of the Kremlin, State Department says.

Russian mercenaries in Libya are fighting not for territory, but to sow the type of international discord that Moscow thrives on, experts told Just the News.

“Russia’s playbook is to create chaos and exploit what comes of it,” said the Sean McFate of the Atlantic Council international think tank. “Mercenaries are a great way to do that. Russia is using them to that end in Libya.”

As many as 1,200 mercenaries who work for a Russia-based private military company currently are in Libya, according to recent accounts. The men reportedly are fighting to support longtime political figure Khalifa Haftar in his bid to unseat Libya’s prime minister, Fayez al-Sarraj.

The mercenaries work for the Wagner Group, a U.S.-sanctioned organization run by an associate of Russian President Vladimir Putin, Yevgeny Prigozhin, the State Department’s Christopher Robinson recent said. But the Russia specialist also noted that the term “mercenary” in this case is a misnomer.

“Wagner is often misleadingly referred to as a Russian private military company, but in fact it’s an instrument of the Russian Government which the Kremlin uses as a low-cost and low-risk instrument to advance its goals,” he said.

The goals are multifaceted, according to the State Department.

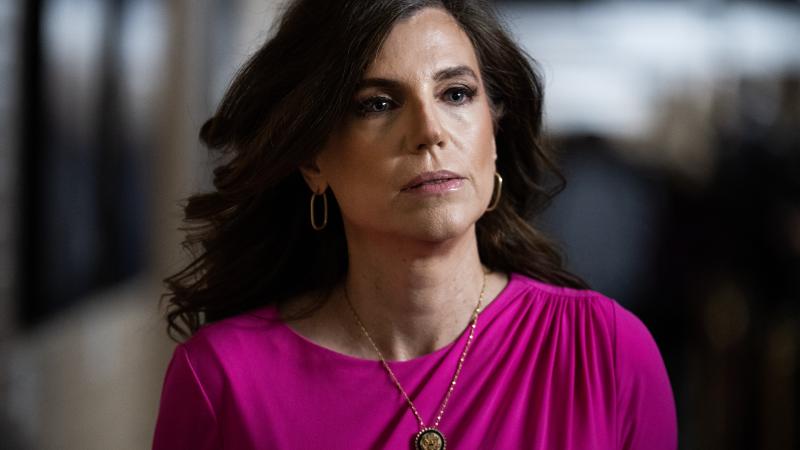

“Russia has exploited instability in Libya to advance its own military, economic, and geopolitical interest in that country and throughout North Africa,” State Department spokesperson Morgan Ortagus said last week.

The goals also are nebulous, experts said.

“To Russia, Libya is a lever of power,” McFate said. “The oil is part of it, but it’s not so much the territory, as what Libya can offer strategically.”

Situated amid key countries in North Africa, coastal Libya is directly across the Mediterranean Sea from NATO members Italy, Greece, and Turkey – a position that Russia can use to its advantage.

“Libya is one of the major spigots of illicit goods and people to Europe,” McFate said. “If it suits them, they can turn on that spigot into the European Union. It creates friction in Europe, and Russia can exploit that.”

For Russia, the key to exploitation is to foment disorder, according to one political analyst.

“Russia does not want anybody to win and restore order in Libya,” said a Frontiers of Freedom senior official, Miklos Radvanyi. “They are interested in chaos in the region.”

Chaos has been a constant in Libya since 2011, when longtime dictator Muammar Qaddafi was killed in an uprising. Among those who helped overthrow Qadaffi was the dictator’s former ally Haftar, who at one time lived in exile in the United States, and who now aims to overthrow the current government.

Haftar has used Russian mercenaries as an “effective force multiplier,” according to a United Nations report that was leaked last week – an assessment with which the State Department agrees.

“Russia’s surge in support to [Haftar] has led to a significant escalation of the conflict and a worsening of the humanitarian situation in Libya,” Robinson said.

Fighting between the opposing factions recently grew more intense, to include clashes over the weekend in Tripoli and at Mitiga Airbase, the city’s main civilian and military airport. At least three people reportedly were killed, and more than a dozen wounded. Passenger aircraft and fuel tanks were damaged.

Earlier this year, Putin denied sending mercenaries and said that any Russians in Libya were there on their own volition.

That explanation, McFate said, is one reason Moscow employs mercenaries.

“It’s built-in deniability,” he said. “It’s a way for Russia to fight in the shadows, when to fight openly would be a problem for them. If problems arise, Russia can walk away from them.”

The Russians are augmenting their hired-soldier forces with outside mercenaries, the State Department’s Robinson said.

“More recently, Russia in coordination with the Assad regime has ferried Syrian fighters to Libya to participate in Wagner operations in support of [Haftar’s forces],” Robinson said.

Some have questioned what the Wagner Group militarily can accomplish.

“They can kill but they cannot win,” Radvanyi said. “Or, they can win but what can they do once they win?”

“They don't need to win,” McFate said. “They just need to create friction. It adds to their toolkit.”

On Wednesday the United Nations Childrens Fund called for a ceasefire in Libya, saying that the violence and the COVID-19 pandemic present a significant threat to life. In the past nine years, the agency said, more than 400,000 Libyans have been displaced by the conflict.

Some 1,000 people have been reported killed in Libya during the last year.